The following is an excerpt from “Fragments III: Democracy, “ a journal from T’ruah.

The term “Israelite,” when applied to Afro-Jewish communities operating outside of the mainstream of rabbinic Jewish life, has a long history and refers to a diverse spectrum of present-day communities and practices in the U.S. Yet media accounts today typically mention Hebrew Israelite communities only when discussing specific adversarial sects.

Scholar and rabbi Dr. Walter Isaac offers a deeper view of this history. His research on the 18th-century Caribbean, for example, reveals a multilayered society in which some mixed-race children of Jewish slaveholders inherited land and authority, people of West African descent passed down memories of Igbo Jewish identity, and those enslaved by Jews integrated Jewish practice as they shaped their religions and identities, during and after their experience of human trafficking. Meanwhile, Jewish slave owners — though few in number compared to Christian ones — lived with the ethical contradiction of owning human beings while practicing a religion that espoused freedom, as well as with fear of persecution from Christian authorities. The influence of all of these interactions persists in independent Afro-Jewish communities today, including many who are outside the frame of U.S. media.

In preparation for Juneteenth this year, T’ruah was honored to host Rabbi Isaac, a leading scholar of Africana Judaism at the University of Tennessee, to discuss the throughline of independent Afro-Jewish communities in the Americas and their long engagement with democratic thought. Here, he explores these ideas in conversation with Rabbi Koach Baruch Frazier. This interview, an excerpt of a longer conversation, has been edited for clarity.

You can find Rabbi Isaac’s Juneteenth lecture, “How Black Jews Helped Invent American Democracy,” here.

Below is a conversation between Rabbi Walter Isaac, PhD, and Rabbi Koach Baruch Frazier.

Rabbi Koach Baruch Frazier: You offered a really thought-provoking lecture this year for Juneteenth. Can you share with us a glance at what your thesis was, and some of the history that forms your thinking?

Rabbi Dr. Walter Isaac: I gave a few instances where African Americans interpreted Judaism as a potentially revolutionary and democratic force in modern history. From the colonial period to the present, whether in French or English or Dutch colonies, you see Afro-Jewish communities campaigning for anti-oppressive policies and social practices.

The role these Jews have played in leading and supporting liberation movements should be studied and investigated more often. Take, for instance, the conversations amongst 18th-century French government officials expressing alarm about the fact that Caribbean Jewish planters were teaching and instructing the Africans they owned in Judaism, [presumably including] holidays like Passover that celebrate freedom from slavery and Jewish self-determination.

KBF: Thinking about how a slave owner might be “instructing” the people in Judaism, particularly around Pesach, as they were enslaving people — I don’t understand the mental gymnastics that one might have to engage in, in order to do that.

WI: Yeah, it doesn’t make sense. It makes no sense.

KBF: To circle back around to the flow of ideas across cultural lines, I hear non-Black Jews today who have the unmitigated gall to talk about the spiritual, “Go Down Moses,” and say, “Well, they [Black communities] took our story. So why can’t we use this song at our seder?” I don’t know what that evokes in you.

WI: One of the things that in my dissertation I problematize is the notion of thinking about one’s heritage in the same way that one thinks about one’s personal property. When I say, “Okay, Judaism is mine,” that’s my spiritual heritage. It’s not the same as me saying, “Judaism is like my phone. I put it in my pocket wherever I go. I paid a lot of money for it. There’s people running around stealing Judaism left and right. I had to put a little lock box on it.” You know what I’m saying? It’s just not how a heritage works. The way we use the possessive case when we talk about human heritage is often a multilateral form of possession, especially when you’re talking about Middle Eastern and African cultures. With “my” Judaism, it’s not a personal possession. It’s a personal, impersonal, and a reciprocal possession all at the same time. So the Judaism owns me more than I own Judaism. It’s mine by virtue of the fact that the tradition has enveloped and embraced me, encasing itself into my existence.

But there’s many ways that can happen. And not all of those ways are wholesome. And so people who’ve been embraced by our heritage in not so-wholesome ways [such as exposure through human trafficking], we have had to find ways to turn that embracing into a kind of affirmation that we can give to our kids, that doesn’t repeat the non-wholesome ways it came into our being. So when somebody says, “They took our Judaism” — yeah, we got a long way to go, Rabbi.

“Rabbinism tied itself to the history of the West and Western ideas. …There’s a long tradition in white European philosophy of talking about the relationship of rationality to enslaved people. But to a lot of Black people, those are really stupid arguments. Their relationship was not, ‘Can I be rational?’ No. Their relationship was, ‘Because I’m rational, what can I do to abolish slavery?’”

KBF: I’m excited to talk to you specifically about human rights, how they are foundational to Hebrew Israelite theology and worldview, and what it looks like to see Hebrew Israelite theology in action.

WI: There’s a long tradition in white European philosophy of talking about the relationship of rationality to enslaved people, such as the philosophies of people like Francis Hutcheson or the arguments about rationality and slavery in the writings of Immanuel Kant. But to a lot of Black people, those are really stupid arguments. Their relationship was not, “Can I be rational?” No. Their relationship was, “Because I’m rational, what can I do to abolish slavery?”

There are differences between human rights discourses coming from modern European traditions and African traditions. From the Israelite standpoint, I think it’s safe to say that we have to quit thinking of human rights as something that’s progressive and start thinking of it as something that’s pretty freaking conservative. If you have people who are saying, “We are deserving of human rights,” it’s probably because they don’t have any! So that kind of world, where we need to talk about human rights, is actually not as progressive as it needs to be. That’s very, very baseline.

I think one of the things that has been neglected in historical research on Black religion is what African Americans are actually saying and doing religiously and spiritually by the dawn of the Civil War. We should listen to what people said about themselves, not what we “think” they were saying. And there are actually many, many records of what so-called slave preachers and what enslaved Africans were saying to each other during the antebellum period.

[For example,] when Colonel Wentworth Higginson observed companies of Black soldiers who were liberated from a part of Florida where Jewish planters were conducting business, he noticed that their religious faith used a bunch of concepts in ways he wasn’t familiar with. They kept talking about something called this “gospel army,” yet they didn’t want to hear anything about Jesus. They were annoyed when people brought Jesus up. And what he found was that this was a manifestation of some kind of mysticism. He was a seminarian, a Harvard Divinity School trained minister. So this was somebody with a lot of knowledge of the Bible. And yet he couldn’t figure out why they were talking about being Hebrews.

He also couldn’t figure out why they talked about Moses as though he was not one historical figure. They had some belief in reincarnation. Every time a leader pops up and they lead people to some sort of freedom movement, the folks that he saw were interpreting that person as a kind of “Moses” figure. According to him, they believed that you could really interpret human history as one long repetitive reiteration of cycles of oppression and liberation using the five books of Moses. And he didn’t know where this was coming from. He could never figure out why these “Black” people were thinking of themselves as Jews and why they did not want to have anything to do with white Christianity.

There’s records from the regiment’s military chaplains where the military chaplain is trying to spread Christian belief: “Jesus is the son of God. Jesus is the Messiah,” and all this sort of stuff. And these Israelites, the Black soldiers, were trying to convert the chaplains to their religion. They said, “No, no, no, no, no. This Christianity stuff — you are confused, man! We’re living in prophecy today. The Bible talks about how, today, God is going to make this world right. God is going to bring us out of captivity. It’s not going to be pretty. But God is going to bring us out of captivity, back into the land of our ancestors.”

Now Colonel Higginson, he used the word “Jewish” to describe their thought-processes because that was the only word that he had. But today, we refer to these people as Hebrew Israelites. And what’s different [between Israelite and rabbinic communities] is that the Israelites used their lived experiences as enslaved peoples as a way to confirm, constantly, the belief that redemption from God is imminent.

In a lot of Rabbinism, the Messianic Age is kind of out there. It’s distant. It’s something we’re constantly praying for, but it’s like, “Someday, eventually.” Whereas in the African American community, when you look at how people interpret the Torah, you see that we interpret the Torah through the liturgical lens of contemporary events. And those events that people look for are almost entirely the events that give the faithful confidence that the prophecy is actually coming true; that keeping the Torah is making the world a better place; and that oppression and slavery will come to an end.

KBF: People see Hebrew Israelites and say, “Oh, they aren’t Jewish.” Yet, there are major reasons why these Afro-Jewish communities don’t have allegiance to rabbinic Judaism: because of the ways it was intertwined with slavery. And I would argue that the perpetuation of human trafficking isn’t Jewish. You’ve spoken about how both Israelite and rabbinic communities looked to Torah as a guide to go against the grain of colonial/capitalist norms of the day. In what ways today do you see Torah having the potential to cause transformation in our present systems?

WI: In order to understand how indigenous African American spiritual traditions developed, we have to get out of the mindset of thinking that colonial-era plantation life was simply a kind of glorified farming endeavor. Yes, producing sugar and indigo and rice and so on are crucial aspects of large-scale plantations. But sex trafficking and death-defying labor were also everyday components of the New World’s plantation complexes. In other words, if people today were suddenly dropped in the middle of an 18th-century sugar plantation in Haiti, they would likely see what we today would call a forced labor death camp.

Therefore, to understand Black American spirituality, you have to see it against the backdrop of many, many people who are resisting acute conditions of oppression, exploitation, and genocide. Such people are not standing idly by, allowing themselves to be used at every desirous whim of Europeans. Our ancestors fought back, and they did so using everything they had available — including their knowledge of Torah.

Israelite communities today have a great deal to contribute theologically and philosophically to the rest of global Jewry. Groups like ours are disproportionately survivors of slavery. Judaism is supposed to be a religion that teaches us, as Jews, how to live as a free people. The word Torah means “teaching.” And I come from a long line of educators. My cousins are teachers. My parents were teachers. My grandfather and namesake, Walter Isaac, was a teacher. In fact, he was almost murdered by a lynch mob in Georgia for teaching other African Americans to read. So education is something that is very important to me and people in my family.

I think what has bound the antebellum-era Israelite communities to the Israelite communities of today was an emphasis on the Torah as a teaching document, and specifically the need to teach and learn how and when certain oppressive practices and institutions should come to an end. Interpreting Torah through studying how contemporary events reveal the slow dismantling of global tyranny is something I have seen over and over again in my interactions with Israelite communities across America.

The Torah teaches us that oppressive practices and traditions always have a shelf life. But often when you ask progressive Jews about how the Torah can help us in the fight against oppression today, they only talk about the [positive] traditions of law and prophetic justice that are found in Judaism. The assumption is that if we learn those principles of law and justice, it by default results in us practicing them. But one thing that I have noticed in Israelite communities is that they have always recognized the flaw in this thinking. Simply being educated in a religion doesn’t make you committed to human dignity. For centuries, Israelites have emphasized a revolutionary approach to embodying those principles, by reminding us that learning about justice is a twofold process: We not only have to learn how to embrace justice, we also have to unlearn our embrace of injustices. And those two things are not the same.

KBF: There are some in the Jewish community who think that there’s only one way to be Jewish. And because of this, they can’t understand what I have heard you call the “creolization” of Judaism in Hebrew Israelite life, between African culture and Jewishness. And I believe that inability is actually antithetical to Judaism. But I also think it’s antithetical to democracy, because democracy has less to do with “we’re all the same” and more to do with how we are across our differences. I’m wondering whether or not you see any connections between those two.

WI: For people who question this creolization with African traditions, I challenge them to really look at the liturgical structures of a lot of Hebrew Israelite congregations. They pull from a great deal of rabbinic literature. There is cross-fertilization of religious traditions and rituals and laws between African Hebrew communities and rabbinic communities.

However, the added component with respect to creating a democracy has to do with creating institutions that realize people’s equality. And it’s the lack of those institutions that disproportionately leads a lot of Hebrew Israelites to distance themselves from participation in the dominant [Jewish] society.

And I think this is where Israelite communities and Rabbinism depart. There’s an ideological thrust in rabbinic Judaism to be able to embed Jewish life safely in the laws of the lands in which Jews live while they are in diaspora. So assimilation, to a very limited extent, is a part of Rabbinism. But in the case of Israelite communities, that assimilation led to human trafficking. And so Israelite communities are presented with a very, very different question: If assimilation means we have to literally dehumanize the “other,” what alternatives do we have that realize coherence between our cultural practices and the values that we hold dear? What is left?

You can’t just build an institution and say, we built this institution for social justice, and then imagine to yourself that because its foundations had good intent, it’s always relevant for any given future situation. There might come a time when that institution may not function in a way that reinforces social justice. We have to be able to recognize that moment.

I think what rabbinic communities are doing — and it’s not really their fault — especially in the last 500 years, is that they’ve been responding to global antisemitism. And so rabbinic Judaism is trying to keep Jews safe. It’s trying to create institutions and spaces that will protect Jewish people’s integrity, that will preserve Jewish people’s values. The problem is that people change, and antisemitism changes. Just because something [such as ancient toleration of slavery] looks just in one time period, it doesn’t mean it always will be just.

My teacher, Dr. Lewis Gordon, used to say that one of the consequences of colonial thinking was the belief that institutions, once constructed, should exist forever and always. But this is really odd when you think about it. What institutions do you know of that are truly eternal? An institution that was relevant a thousand years ago may not be as relevant today, and its existence today may actually make the world a worse place to live in. Perhaps the situation has changed and whatever caused the need for that institution a thousand years ago has vanished or become irrelevant. If so, then why should we assume it’s good to use all our energy maintaining it?

To be clear, I’m not trying to be disrespectful of the labor that our ancestors exerted to make the world a better place. Our survival as a people is undoubtedly indebted to the historical power of Rabbinism’s innovations, for example. My point is actually quite the opposite: We honor our ancestors by learning how to make the world a safer, kinder, more just place for our progeny to inhabit. And when you think about it, that simple message of making the world better for our children by unlearning injustice and slowly and deliberately dismantling unjust institutions is quite revolutionary.

Israelite communities came into existence because there were people who could not recognize when rabbinic precedent was no longer healthy for the Jewish community. People were exploiting those laws and in many cases ignoring those laws in order to practice human trafficking. So indigenous forms of African American Judaism, including many Israelite institutions, emerged in response to that situation. Because slavery had to come to an end, and Jewish law was ineffectual in doing it. It was Israelites who recognized that modern slavery demanded a revolutionary approach to Jewish traditions — without assuming they were always bad traditions just because they had to come to an end.

KBF: The era you’re examining was formative for the identities of Black Jewish, or Israelite, communities in the Americas. It also seems to be a time when white Jewish identity was going through a rapid formation. Could you tell us about how Western Sephardim who fled European Inquisitors established their racial status through interaction with Black Israelite communities and white Christians? Are there things this might illuminate about present-day white Jewish identity?

WI: This is actually a very complex question, because it not only deals with the history of antisemitism in Europe, but also how that history of persecuting Jews metastasized into racial divisions in global Jewry today. For example, if a European Jew wanted to escape persecution by assimilating into their European identity, and a crucial aspect of European identity was to express superiority over Africans — say, through slavery — then European Jews could appear as fully equal and European through enslaving Africans.

That’s simple enough. The problem arises when we forget that Africans in the Americas also recognized the preponderance of antisemitic racism in the Americas. Most Africans in the colonies may have been enslaved, but being enslaved didn’t mean they had no power whatsoever. There were many opportunities to take vengeance on an abusive Jewish slave owner by whispering in the ears of an Inquisitor, or other antisemite, that such owners were secretly defying the Church and plotting against white Christian colonists. And so Jewish and New Christian slave owners had great incentive to develop a reputation for being less abusive to their Africans than non-Jewish slave owners. By giving their Africans a little more liberty, they could buy a Black person’s silence.

Some years ago, I wrote a piece that was critical of a work by Rabbi Bertram Korn. He wrote on Jews and slavery in the U.S. South, and he actually had the gall to say that, well, some of these slave owners were actually kind of nice to the people they owned. The most charitable reading I can give to that is this: Black people were intelligent. And we recognized during slavery that not all white people were the same. As a matter of fact, this shows up time and time again in slave narratives, where people were asked, “What was your life like? Who was your owner? How did they treat you?” A lot of times in slave narratives you will have African Americans saying things like, “Oh, well, Master Tom, he was a good master.”

Okay, first of all, let’s get the context straight. That doesn’t mean the person being interviewed thought slavery was good. What that meant was the person was thankful because their owner did not work them literally to death. So when Korn makes this comment that Jewish slave owners were pretty good (the eye rolling is appropriate!), I think he was saying that Black people who were being trafficked recognized that other Europeans considered Jewish Europeans to be inferior, to the point of persecution.

There are other slave narratives, even from the Caribbean, of Black people going to Jewish people and saying, “You know what? We should join forces. They don’t like you, either. Why are you trying to be like those people?” And the reason is obvious. Black people are going to use everything at their disposal to try to bring these human trafficking networks to an end.

If you were a Jewish slave owner [under Catholic rule] during the colonial period, it wasn’t in your best interest to be cruel to Black people such that they would go to the Christians to bring the Inquisitors out. I think that is why Bertram Korn made the comment that he did. He was noticing that there were certain things Jewish slave owners were doing that Christians were not. Jewish slave owners were giving [enslaved Africans] days of rest on both Saturday and Sunday. Jewish slave owners were allowing Africans to eat certain foods that Africans owned by others were not allowed to eat. And because Jews were vulnerable [in ways that Christians were not], Jewish slave owners would oftentimes sell, or purchase, or inherit the Africans they trafficked to, or from, or with, other Jews. And so not only were Jewish people in colonial America engaging in economic activity with each other; enslaved Africans connected to those Jewish families were engaging in economic and cultural activity with each other. And this was creating two parallel types of Jewish communities in the Atlantic world.

But let’s be clear: Recognizing this history doesn’t romanticize it. Ain’t no such thing as good human trafficking. None of this is redeemable. None of it. And yet, what you still have are Jews of all colors trying to stay true to their heritage. Constructing new families, constructing new rituals of meaning and purpose, and surviving. And those things — the wholesome things people did to survive — are what I think we should preserve and honor and respect.

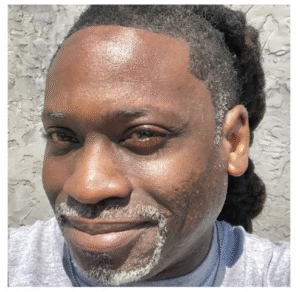

RABBI KOACH BARUCH (KB) FRAZIER (they/he) is a transformer, heartbeat of movements, healer, musician, founder of the Black Trans Torah Club, co founder of the Tzedek Lab, and co-founder of Black Folks Beit Midrash. A collaborative leader, rooted in tradition, curiosity, and love, Koach strives to dismantle racism, actualize liberation, and transform lives both sonically and spiritually.

RABBI WALTER R. ISAAC, PHD (he/she/they) is an African American rabbi who was raised in the Gullah/ Geechee lowcountry. He is of Afro-Mizrahi descent and is affiliated with both Hebrew Israelite and Jewish communities. He has been a Research Fellow in Africana Studies at Brown University, as well as the Program Director for Temple University’s Center for Afro-Jewish Studies, and is the current President of both the Afro-Jewish Studies Association and the Olaudah Equiano Institute. His research has recently focused on the development of modern democracy from Jewish communities of color in the Americas. Currently he is a Lecturer in the department of Africana Studies at the University of Tennessee.