A firsthand account from Rabbi Jill Jacobs, T’ruah Executive Director, of the joint T’ruah-HIAS border delegation, November 2019.

I just returned from El Paso, where T’ruah and HIAS jointly brought a group of 23 Jewish leaders—rabbis, one cantor, and the Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary—to witness the desperate situation on the Mexican border, and to bring our collective moral voice to stand with immigrants and asylum seekers. We heard over and over from advocates on the ground that they hear legal voices and policy voices, but are desperate for a moral and religious voice. That’s why we went, and that’s why I’m writing to you to let you know what we saw. This email will be long, but I know that you—as part of the T’ruah family—are committed to knowing and speaking about human rights abuses, including on our border. You deserve the full picture, the one that is more than talking points and highlights.

We traveled to Ciudad Juárez, El Paso’s sister city in Mexico. As we heard from every El Paso resident who spoke with us, these two cities are one metropolitan area, where for decades, tens of thousands of people have gone back and forth each day, to go to school, to work, to have dinner, and to see family and friends.

The United States has recently implemented what the President calls a “remain in Mexico” policy, by which those who apply for asylum at a port of entry are sent back to Mexico to wait for their asylum hearings. Currently, 55,000 people have been sent back to Mexico to wait. That number makes this area one of the ten largest refugee camps in the world.

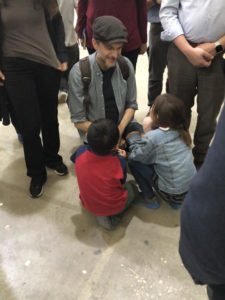

We visited one shelter housing some of these asylum seekers. This shelter, run by the Mexican government, currently houses more than 650 people, 40% of whom are children. We spoke to one woman from Honduras who fled with her 15-year old daughter after gangs threatened to kill them both, in part because of her volunteer work with USAID. Along the way, she was kidnapped by gang members, but escaped, and presented at a port of entry—as asylum seekers are supposed to do. She received a “credible fear” interview, the first step in the asylum process, and was sent back to Mexico to wait. She has seen members of the gang that threatened her around the shelter, and is terrified to leave the building.

We visited one shelter housing some of these asylum seekers. This shelter, run by the Mexican government, currently houses more than 650 people, 40% of whom are children. We spoke to one woman from Honduras who fled with her 15-year old daughter after gangs threatened to kill them both, in part because of her volunteer work with USAID. Along the way, she was kidnapped by gang members, but escaped, and presented at a port of entry—as asylum seekers are supposed to do. She received a “credible fear” interview, the first step in the asylum process, and was sent back to Mexico to wait. She has seen members of the gang that threatened her around the shelter, and is terrified to leave the building.

These asylum seekers can wait 6-9 months or more, trapped in shelters in a city where traffickers target migrants who venture outside. We heard over and over that these asylum seekers would prefer to be in ICE detention in the US than stuck in Mexico.

By the bridge to the United States, we saw a tent city that has sprung up over the past few months. The estimated 3,000 people living there are Mexican nationals waiting to apply for asylum. Thanks to a new “metering” program by which the US only allows a certain number of people a day to apply for asylum, these families and individuals are stuck waiting months for their number to be called. Currently, there are 20,000 people on the metering list, with as few as 15 being called each day. Yesterday morning, as I watched a sudden hailstorm from the comfort of my hotel room, I could think only of these families exposed to the elements for months on end, just because they are following the legal process to apply for asylum.

By the bridge to the United States, we saw a tent city that has sprung up over the past few months. The estimated 3,000 people living there are Mexican nationals waiting to apply for asylum. Thanks to a new “metering” program by which the US only allows a certain number of people a day to apply for asylum, these families and individuals are stuck waiting months for their number to be called. Currently, there are 20,000 people on the metering list, with as few as 15 being called each day. Yesterday morning, as I watched a sudden hailstorm from the comfort of my hotel room, I could think only of these families exposed to the elements for months on end, just because they are following the legal process to apply for asylum.

On our second day, we visited the Otero detention center in southern New Mexico, about an hour from El Paso. This is a private facility, run by MTC (Management & Training Corporation). Their motto—displayed on giant posters throughout the facility—is “Believe it or not I care”—”Bionic” for short.

It was hard to believe.

This is not a criminal facility, but a civil one, holding people who are awaiting asylum or deportation hearings. From the barbed wire surrounding the facility, the jump suits worn by those inside, and the bars and cells throughout the facility, it was hard to remember that the people inside have not been charged with any crime.

This is not a criminal facility, but a civil one, holding people who are awaiting asylum or deportation hearings. From the barbed wire surrounding the facility, the jump suits worn by those inside, and the bars and cells throughout the facility, it was hard to remember that the people inside have not been charged with any crime.

We received a sanitized tour from an ICE public relations official and the warden, who boasted to us of the safe conditions and the educational programs inside the facility. Cliche inspirational quotes papered the walls of the staff area, along with signs about staff appreciation events like a “fancy manicure” event. Some staff members wore purple ribbons for anti-bullying month.

Detainees can work for $1 a day inside the facility. An international phone call costs 35¢ a minute.

This is a facility in which Punjabi detainees recently carried out a hunger strike in response to poor conditions, including the lack of vegetarian food, and were placed in solitary confinement and force fed in contradiction of international human rights law. And it’s a place where several Cuban asylum seekers have recently attempted suicide and where guards threatened to shoot asylum seekers who carried out a non-violent sit-down strike—and then placed these asylum seekers in isolation.

And yet, when we asked about solitary confinement, the warden told us that they don’t use this punishment much, mostly use solitary for the protection of detainees, and that some detainees request it because “they just like to be alone.” Per international law, isolation of more than 15 days is considered torture.

We continued on to the federal courthouse, where we saw a quick trial of four men arrested for crossing the border not at a port of entry. This is a misdemeanor, on the level of a traffic violation. Yet these men appeared in handcuffs and jumpsuits. All pleaded guilty (the only real option) and received short sentences (from time served to 10 days). But that doesn’t mean they’re done—it means that they’re now headed to immigration court and will wait for their hearings in Otero or a similar detention center. One of these men told the judge that he has been in the US for 12 years, and that his wife and children live in Dallas. (He presumably went back to Mexico for a visit and got caught returning.) Now, he’s likely to be deported and separated from them.

Our group studied together the talmudic and midrashic descriptions of Sodom, the paradigm of the evil city. Per the Talmud:

“The Sages taught: The people of Sodom became haughty due only to the excessive goodness that the Holy Blessed One bestowed upon them…

They said: Since we [have] a land from which bread comes and has the dust of gold, why do we need travelers, as they come only to take away our property? Come, let us cause the proper treatment of travelers to be forgotten from our land…”

The rabbis go on to describe the people of Sodom as engaged in wanton cruelty toward foreigners, including torture and the punishment of anyone who offers humanitarian relief. (Sanhedrin 109a)

Our country has become Sodom—a place that refuses to see asylum seekers and immigrants as human beings, and that engages in random cruelty that serves no humanitarian or economic purpose.

Thankfully, we also saw good people standing on the side of righteousness. When Abraham pleaded with God to save Sodom if only 10 righteous people could be found there, the city failed even to meet this low threshold. But in El Paso, we met immigration attorneys working day and night to help their clients gain refuge, volunteers feeding and housing those who made it across the border, elected officials working to change laws to protect immigrants and asylum seekers, and ordinary El Paso residents refusing to give in to hatred.

Thank you for being one of these thousands of people bringing your own moral voice to insisting that our country can no longer be Sodom.

For now, I hope you’ll share this story with your colleagues, community, and elected officials. In the next weeks, we will reach out to you with actions you can take to protect immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees.