The following is an excerpt from “Fragments III: Democracy, “ a journal from T’ruah.

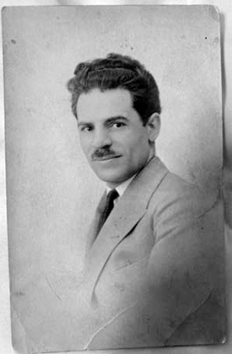

In 1912, 19-year-old Raphael Hasson fled the carnage of the Balkan Wars in his native Salonica and sought refuge in the United States. Hasson was not alone in leaving Salonica, an Aegean port city once home to the largest Sephardic Jewish community in the world. Around 50,000 mostly Ladino-speaking Sephardic Jews from the Ottoman Empire and its successor states arrived in the United States during the early 20th century. Yet in a new country whose Jewish immigrant population was overwhelmingly Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe, Hasson and his fellow Ottoman Jews faced a series of barriers upon their arrival. Officials could not readily classify them: Were they “Hebrews,” Turks, Greeks, Arabs, Spaniards, Italians, or Puerto Ricans? Europeans or “Asiatics”? White or brown? Due to differences in languages, cultures, customs, names, geographic origins, and appearances, Yiddish-speaking Jews insisted that the newcomers could not possibly be fellow Jews, going so far as to denigrate them in the press. The alienation experienced by Sephardic Jews even led former president Theodore Roosevelt to characterize them as “peculiarly helpless” and the “lowest and poorest paid workers” in all of New York City’s garment industry in 1913.1

Photograph of Raphael Hasson in New York, 1925 (courtesy of the Hasson family).

At 19, Hasson was already a seasoned activist. Having participated in Salonica’s Socialist Workers’ Federation (est. 1909) — the largest organized labor movement in the Mediterranean region — he recognized that the United States was not a promised land, but rather was rife with class exploitation and racial oppression. In Salonica, the Federation had developed a multinational approach to organizing and brought together Jewish, Turkish, Greek, and Bulgarian workers. Hasson and other Jews who had been active in Salonica’s Federation now drew inspiration from their prior political activism to form bonds of solidarity with working class people in their new country of residence. Hasson and his kompanyeros (“comrades”) applied the Federation’s multinational principles to the context of the American empire. Whether allying with Puerto Ricans in New York or Greeks in Chicago, Hasson reiterated the Federation’s internationalist imperative: the “emancipation of all peoples.”2

When Hasson finally made his home in Chicago, during World War I, he set to work forging alliances with fellow Ottomans and fellow Spanish-speakers. Beginning in 1917, he established the Chicago Socialist Party’s Spanish Section, uniting not only Sephardic Jews and other “Spanish-speakers” (likely Mexican Catholics) but also fellow Ottomans who were being maligned as “modern white coolies” — Armenians, Turks, and Bulgarians.3 The group formed a small multilingual library, held members’ dances and discussions on socialism and unionization, participated in mass rallies, and regularly reported on their activities in New York’s Ladino socialist newspaper, La Bos del Pueblo (The Voice of the People).4 They also hosted guest speakers like socialist alderman William E. Rodriguez, the first Hispanic official elected to local office in Chicago, enhancing connections among Ladino- and Spanish-speaking workers in the city.

In 1919, Hasson drew once again on his multilingualism to play a key role in forming the Greek Federation of the new Communist Party of America. Circulating pamphlets in Greek to raise taxisinidisia (“working-class consciousness,” in Greek-American parlance) among Chicago’s exploited Greek workers, the group recruited from the local Greek Orthodox Christian community and met at Chicago’s famous Hull House.5

Just as the Ottoman state had arrested and exiled leaders of Salonica’s Socialist Workers’ Federation, so, too, did the U.S. government view the organizing work by Hasson and others as an existential threat. At the close of World War I, the first Red Scare resulted in the squashing of radical and labor movements across the country. Hasson was among those arrested and interrogated by federal agents.

Somehow avoiding deportation, Hasson fled to New York. There he joined the newly established Sephardic Branch of the Workers’ (Communist) Party in 1921. He made overtures to Yiddish-speaking comrades, but Hasson’s effort to establish a Ladino-speaking section of the Workmen’s Circle faltered. Instead, in Harlem, Sephardic activists forged alliances with Puerto Ricans in the garment industry. Together, in 1929, Sephardic and Puerto Rican activists reformulated the Sephardic Branch of the Workers’ Party as the Spanish Branch.

When Hasson passed away in 1948, he was given a glowing eulogy from a fellow Salonica Socialist Workers’ Federation veteran and leader of the Sephardic Brotherhood of America, a mutual aid organization in New York. Haham Albert Matarasso had been a socialist and, as his rabbinic title denoted, a graduate of Salonica’s rabbinical seminary. Matarasso remembered Hasson as a man committed to organizing, dedicated to his community, and a pious synagogue-goer who, before taking his last breath, recited the viddui, the traditional deathbed confessional prayer.6

What lessons do Hasson’s experiments with grassroots coalitions offer us as Jews several generations later working to envision a vibrant multiracial democracy in the United States?

The Vertical Alliance

In many ways, successful protective grassroots alliances with non-Jews are an anomaly in Jewish history. In the face of persistent vulnerability as a diasporic community in virtually every time and place since antiquity and continuing into modern times, Jews at many times in history have surmised that their safety and well-being could not be entrusted either to their suspicious non-Jewish neighbors or the caprices of local authorities. Jewish communal leaders in ancient, medieval, and early modern communities, tasked with keeping their communities safe, turned to kings and potentates who offered the privilege of protection in exchange for taxes, useful skills, loyalty, and gratitude.

In the wake of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, the noted chronicler Solomon ibn Verga settled in Edirne, in the Ottoman Empire, and described this communal practice in a way that has influenced scholars since. In a treatise called Shevet Yehuda (The Scepter of Judah, 1554), Ibn Verga chronicled persecutions experienced by Jews across the generations and articulated the prevailing political theory of Jewish communal leadership, which scholars describe as the “vertical alliance.” As the late historian and noted exegete of ibn Verga, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi writes Jewish communal leaders sought a “direct vertical alliance, even if this meant alienating lower officialdom and [even if it] was forged at the expense of horizontal alliances with other segments or classes of the general population.”7 It was safer to bypass local authorities and populations — whether non-Jewish peasants or merchants — than to stake the community’s safety on them.

With the opening of the modern era and the beginning of mass social movements, differences of opinion came to light within Jewish communities about how best to seek safety. Should Jews maintain relationships with the highest authorities of the land in hopes of protection, or seek alliances with other oppressed groups in order to secure rights together? Jewish socialist movements, such as the Jewish Labor Bund (the major secular Yiddish socialist party in the Russian Empire, established in 1897), chose the latter. Bundists believed that Jews could only be free in a socialist society that freed all people. As such, they sought out horizontal alliances with non-Jews to fight for revolution and the liberation of all oppressed people.

But Jewish attempts at horizontal alliances, such as the efforts of Bundists, often met with frustration. On one hand, persistent, classical antisemitic teachings undergirded workers’ and revolutionary movements that painted Jews as a wealthy class of exploiters — despite the vast poverty affecting Jews in many of the regions where these movements emerged. On the other hand, non-Jewish Leftists were prone to a more “enlightened” erasure of Jewish particularity. Although Jews were overrepresented in the ranks of socialist and communist movements, those movements tended not to recognize Jews as Jews, with worthwhile identities or specific needs. Socialist and communist leadership erased the particular problems confronting Jews in the name of universal class solidarity. In the face of the universalism of Leninist socialism, determined Yerushalmi, even the Bund failed in its efforts to secure Jewish national rights.8

Jewish communal leaders, including emerging Jewish middle classes, fell largely on the side of continued alliance with higher authorities. As Jews increasingly gained civil and political rights in the countries in which they lived, they embraced the rhetoric of modern patriotism. Jews in Germany claimed status as Germans; those in Austria as Austrians; those in France as French. In the Ottoman Empire, Jews sought to refashion themselves as the “most loyal” Ottomans, in part by orchestrating celebrations across the empire in 1892 not to mourn their forebears’ expulsion from Spain in 1492, but rather to celebrate their arrival in the Ottoman realm and the protection granted to them across the generations.9 In varied national contexts, Jewish leaders’ expressions of patriotism merged a sincere belief in the ability of their states to protect them with an undergirding sense of vulnerability. In the Ottoman case, Jews’ expressions of loyalty reached a fever pitch in the 1890s, precisely as their Armenian neighbors became the targets of state-sponsored mass violence.

As a new international system of states emerged in the 19th century, Jewish leaders like Moses Montefiore and institutions like the Paris based schooling system of the Alliance Israélite Universelle recast the vertical alliance by appealing to the imperial powers to secure protections and opportunities in a shifting geopolitical context.10 Leaders of the Zionist movement courted the British empire, which issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917, calling for the establishment of a Jewish national home in Ottoman Palestine. At each phase, the State of Israel’s eventual emergence depended on a vertical alliance: under the British Mandate, with the authorization of the new League of Nations, then the recognition of the United Nations, and finally in Israel’s ongoing reliance on the world superpower of the United States for protection.11

For those scholars who see the absence of state-initiated violence as key to the vertical alliance across the ages, the Holocaust orchestrated by the Nazi state represented an unprecedented calamity. However, it did not completely undercut the willingness of some Jewish leaders to reformulate the vertical alliance in the face of an ongoing sense of vulnerability in a new geopolitical reality.

The American Exception?

For many commentators, the United States emerges as an exception to the rule, encapsulated in the image of America as the goldene medina, as it was known in Yiddish. According to this line of thinking, Jews in the United States could forgo the vertical alliance because they do not require the protection of the state in a pluralistic, diverse, and liberal society where they share the same status as their fellow citizens. In a place like New York City, it is suggested, Jews benefit from the ability to form their own “peaceful urban community” that is “untouched by the grip of the state or by the question of the vertical alliance.”12

However, this deeply entrenched perception of American exceptionalism fails to address the underlying reasons Jews may have experienced more overall security in the United States than in other places. Where the American Jewish experience has been exceptional, it is not because the United States is a more just society, but rather that here Jews have not been the primary “other” targeted by the wrath of the state and society. That status has been foisted upon other groups, primarily Indigenous and Black communities.

Despite these differences, the vertical alliance persisted in American Jewish life. While European-origin Jews never faced exclusion from the right to be naturalized — something available since 1790 only to “free white person[s]” — they did face discrimination and violence in other domains. Precisely due to such an ambivalent dynamic, U.S. Jewish organizations since the early 20th century have continued to pursue the vertical alliance. These organizations attempted to combat antisemitism by cultivating a politics of white, middle-class respectability. Such respectability worked against more “threatening” images of American Jews: the disconcerting leftist Jewish activism that had animated the Yiddish-speaking masses and the racial liability of Ottoman Jews — less European, less white, and generally poorer. As Shane Burley and Ben Lorber have recently lamented, such a strategy remains dominant today, as “our community’s self-appointed leaders seek a ‘vertical alliance’ of proximity to power, whether in a misguided strategy to keep Jews safe, or to protect their own interests…”13

The American Jewish Committee (AJC), the oldest Jewish advocacy organization in the U.S. — established in 1906 by well-to-do Jews of Central European background — took shape to lobby the U.S. government to pressure the Russian state to halt anti-Jewish pogroms and to oppose federal immigration restrictions. Fascinatingly, the AJC’s leader, Louis Marshall, supported Arabic-speaking Syrian Christians’ petitions for naturalization in 1910, not by opposing the law of the land that permitted essentially only white people to naturalize, but rather by claiming that Syrians should be considered white by law too — just like European Jews.14 He did so due to fears that if the courts ruled that Syrians were ineligible to naturalize, perhaps “Hebrews” — fellow “Semites” — would be excluded next.15 The popular New York Ladino newspaper La Vara nonetheless criticized the AJC as an “antidemocratic” institution that did not represent everyday Jews — and certainly not Sepharadim — but instead the “caste” of elite Jews bent on preserving their status.16

The work of other legacy Jewish institutions, such as the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) (est. 1913), reveals just how central the vertical alliance has been for securing not only protection but also privilege for American Jews. The ADL’s mission to “secure fair and just treatment for all” manifested in its support for Brown v. Board of Education and horizontal alliances which contributed to the civil rights movement. But as Jews of European heritage increasingly found themselves recognized as white people — beneficiaries of the G. I. Bill and federal loans after World War II and participants in “white flight” — the trajectories of (white) Jews and communities of color further diverged. The ADL increasingly pursued cooperation with the state, by collaborating with law enforcement, promoting militarized surveillance, and advocating for anti-terrorism statutes and hate crime bills, all of which ostensibly seek protections against antisemitism but disproportionately impact communities of color and drive wedges between Jewish communities and non-Jewish communities of color.17 Sephardic Jews entered the ADL’s purview only in 1973 when the organization supported Marco DeFunis, a Sephardic Jew from Seattle with family roots in Istanbul, to oppose affirmative action at the Supreme Court: DeFunis claimed that he had been discriminated against as a white person by the University of Washington, which had rejected his law school application.18 How the times had changed!

Multi-Rootedness and the Power of Horizontal Alliances

If the Bund provided one model for horizontal alliances, Salonica’s Socialist Workers’ Federation bequeathed a slightly different legacy. Where the Bund had emerged from a society marked by harsh anti Jewish violence and formed an autonomous Jewish movement that sought to advocate for Jewish needs while also allying with workers of all nationalities, the Federation had formed in the Ottoman Empire, where anti-Jewish violence remained minimal. While the leadership and the largest segment of the membership of the Federation were Jewish and defended Ladino as the legitimate language of the local Jewish worker, they sought to enhance the federationalist principle by linking with workers across communities in one shared organization (which eventually became absorbed into the Greek Communist Party). In addition, the Mediterranean-based Federation, like many left-wing movements in the Global South, did not necessarily emphasize a sharp dichotomy between “secular” and “religious.” Rather, they provided their members with opportunities for melding radical politics and traditional religious observance, a dynamic reflected in the life of Raphael Hasson.

Today, Jews in social justice movements continue to find inspiration in these pursuits of horizontal alliance. While critics have found reasons to dismiss the Bund — for example, suggesting that they were unable to retain a strong enough sense of Jewish collectivity while forging class solidarities — many Jewish progressives today find inspiration in the Bundist principle of doikayt (“here-ness”), which demands that Jews in the diaspora (“here,” as opposed to only “there,” in Israel) work toward safety and freedom — for themselves and their neighbors — wherever they reside.19 If the Yiddish principle of doikayt offers one spark of inspiration, the principle of poly-enracinement — “multi-rootedness,” coined by French philosopher Edgar Morin — offers another model that resonates with some of the Federation’s spirit. Morin, a veteran of the communist resistance to the Nazis, was born Edgar Nahoum to Salonican Jewish parents. He sees himself as benefiting from cross-generational Sephardic roots planted in Spain, Portugal, Italy, Turkey, Greece, Salonica, Paris, and the region of the Mediterranean.20 Multi-rootedness imagines not a dichotomy between “here” and “there” — a single homeland versus one diaspora, a center versus a periphery — but rather a fluid and complex relationship between multiple geographies and cultures that may be combined and reformulated in limitless constellations to meet the needs of the present moment.

Raphael Hasson and others associated with the Socialist Workers’ Federation offered a distinct model for horizontal alliances. Yet they also faced a distinct set of challenges. If Hasson and his peers confronted a major shock upon their arrival in the United States, it was not only that the alleged promised land of America was as corrupted by capitalism and racism as any other. The greatest shock was their initial illegibility in American racial and national terms. Although they had been unquestionably Jewish in the Ottoman context, in the United States they could not readily convince other Jews, or non-Jews, to recognize them as Jews. The erasure these activists experienced helps to explain why the story of Hasson has never before been told and why the world of the Ladino left, more generally, remains absent from the annals of American Jewish history and collective memory. Yet Sephardic activists transformed their own illegibility into an asset, as their multiple cultural and geographic affiliations enabled them to build bonds of solidarity with a wide range of communities.

The multi-rootedness of Hasson and his kompanyeros reveals the power that comes from forging horizontal bonds in the style of Salonica’s Federation, which aspired to recognize the cultural and religious distinctiveness of different communities. But to recognize their power requires that we also confront the history of prejudice among Jews that stymied the efforts of Hasson and his peers to find common cause with Yiddish speaking activists. Today, when we as Jews pursue horizontal alliances to forge multiracial, multireligious, and multicultural democracies here, there, and in all the spaces where we are rooted, we must also recognize that our own Jewish communities are multiracial and multicultural. One enduring lesson from the work of these Sephardic activists is that the potential of multi-rooted coalitions cannot easily be fulfilled while racism within the Jewish community saps their energy.

The “we” is multiple: Within the “we” already exist the ingredients necessary to forge bonds of solidarity with others beyond the Jewish community. Jews of Spanish- or Ladino-speaking heritage may serve as a bridge to Latine communities. Those with Middle Eastern roots may build bridges with Palestinian, Arab, or Muslim communities. Jews of color may provide linkages to Black or Asian communities. Jewish communities are uniquely positioned to forge horizontal alliances across difference because our community already contains so much of that difference within. It just needs to be valorized, activated, and championed for our own sake and for the sake of all of those with whom we seek horizontal alliances in the quest for a truly democratic society, everywhere that we are rooted.

NOTES

1 “Roosevelt Urges State Strike Action,” (New York Times, January 25, 1913) p.24.

2 “Adelantre por el Movimiento Sosialista de Shikago,” Raphael Hasson, (La Bos del Pueblo, October 5, 1917) p. 1, 4.

3 “Movimiento Socialista en Shikago,” (La Bos del Pueblo, April 17, 1917) p. 3; On “modern white coolies,” see “The American Socialist Party and ‘New’ Immigrants,” Charles Leinenweber, (Science & Society, Winter 1968) vol. 32, no. 1, p. 1-25.

4 Rodriguez was the first Hispanic person elected to Chicago’s City Council and later founded the local chapter of the ACLU.

5 See “Red America: Greek Communists in the United States, 1920-1950,” Kostis Karpozilos, (New York: Berghahn Books, 2023).

6 Thanks to Hasson’s family for sharing the Ladino-language eulogy with me.

7 “The Lisbon Massacre of 1506 and the Royal Image in the ‘Shebet Yehudah,’” Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, (Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press, 1976) p. xi; “‘Servants of Kings and not Servants of Servants’: Some Aspects of the Political History of the Jews,” Yerushalmi, in “The Faith of Fallen Jews: Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi and the Writing of Jewish History,” David N. Meyers and Alexander Kaye, eds, (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2013), p. 245-276. See also “Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, the Royal Alliance, and Jewish Political Theory,” Lois C. Dubin, (Jewish History, 2014) vol. 28, no. 1, p. 51-81.

8 “Servants of Kings and not Servants of Servants,” Yerushalmi, p. 261-264.

9 “Becoming Ottomans: Sephardi Jews and Imperial Citizenship in the Modern Era,” Julia Phillips Cohen, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

10 “The Vertical Alliance Today,” Samuel Moyn, (Sh’ma, November 2011) p. 18-19.

11 “On Vertical Alliances, ‘Perfidious Albion’ and the Security Paradigm: Reflections on the Balfour Declaration Centennial and the Winding Road to Israeli Independence,” Arie Dubnov, (European Judaism, Spring 2019) vol. 52, no. 1, p. 67-110.

12 “Tears of History: The Rise of Political Antisemitism in the United States,” Pierre Birnbaum (New York: Columbia University Press, 2023); “From Europe to Pittsburgh: Salo W. Baron and Yosef H. Yerushalmi Between Lachrymose Theory and the End of the Vertical Alliance,” Birnbaum, in “Salo Baron: The Past and Future of Jewish Studies in America,” Rebecca Kobrin, ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2022), p. 174-191.

13 “Safety Through Solidarity,” Burley and Lorber, (Melville House, 2024) p. 304.

14 After the Civil War, people “of African nativity,” namely Black people, also became eligible for naturalization, but since Black immigrants remained few in number, whiteness remained a key precondition for most immigrants who sought naturalization. See “White by Law: The Legal Construction of Race,” Ian Haney Lopez (New York: New York University Press, 2006).

15 “Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora.,” Sarah Gaultieri, (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2009) p. 68.

16 See contemporary discussion of how the American Jewish Congress might respond to the elitism of the American Jewish Committee in “La proksima konferensia del Amerikan Djuish Kongres,” (La Vara, May 13, 1938) p. 2.

17 “The Anti-Democratic Origins of the ADL and the AJC,” Emmaia German, (Jewish Currents, March 12, 2021) https://jewishcurrents.org/the-anti-democratic-origins-of-the-jewish-establishment; “How the ADL’s Israel Advoacy Undermines its Civil Rights Work,” Jacob Hutt and Alex Kane, (Jewish Currents, February 8, 2021) https://jewishcurrents.org/how-the-adls-israel-advocacy-undermines-its-civil-rights-work.

18 “‘Sephardic Jewish Persons are Classified as White’: Education, Race, and Sephardic Jews in the 1970s,” Max Modiano Daniel, in “Jewish Identities in the American West: Relational Perspectives,” Ellen Eisenberg, ed., (Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2022) p. 290-325.

19 “Servants of Kings and not Servants of Servants,” Yerushalmi, p. 263.

20 “Introducing Moabet,” Devin E. Naar, (Ayin Press, May 4, 2023) https://ayinpress.org/introduction-to-moabet/.

DEVIN E. NAAR, PHD (he/him) is an associate professor of History and Jewish Studies and chair of the Sephardic Studies program at the University of Washington in Seattle. His first book, “Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece,” won a National Jewish Book Award (2016) and an award from the Modern Greek Studies Association. His current book project explores the histories of Sephardic Jews in the United States through the lenses of race, politics, and culture.