The following is an excerpt from “Fragments III: Democracy, “ a journal from T’ruah.

This is part two of a debate across time between author Ben Lorber and Rabbi Joshua Trachtenberg about American Jews’ strategies to resist antisemitism. Read part one here.

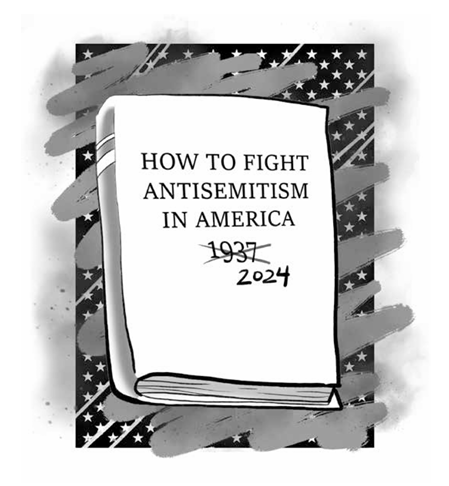

When Rabbi Joshua Trachtenberg contributed his 1937 essay “Stop Fascism: Preserve Democracy” to an anthology called “How to Combat Anti-Semitism in America,” storm clouds of fascism were darkening Europe. Jews faced mounting persecution in Nazi Germany, and fascist movements were on the march in America — but the worst was yet to come. Unlike most rabbis, Trachtenberg lived outside of a heavily Jewish metropolis, in Easton, Pennsylvania, and this likely gave him valuable insight into the bigoted currents sweeping Christian-dominant American society. Six years later, with the war now in full swing, Trachtenberg published “The Devil and the Jews,” which quickly became a canonical analysis, unpacking centuries of Christian anti-Judaism and the persistence of its demonizing tropes in the modern world.

In this early essay, the 33-year-old Trachtenberg describes antisemitism in America as a form of oppression “indigenous to our economic system, which goads the underprivileged” to scapegoat Jews for “the iniquities of the system itself.” In response, he calls for Jews to go and teach gentiles why fighting antisemitism and defending democracy is in everyone’s interest. He outlines a vigorous campaign among ministers, teachers, and publicists to change societal attitudes, unlearn antisemitic biases, and promote democratic ideals.

Trachtenberg’s words remained compelling long after his writing, speaking to the core truth of his observations. In the 1980s, neo-Nazis told rural whites in states like Kansas that an international Jewish banking cabal was responsible for the economic dislocations of the farm crisis. In the 1990s, far-right groups like the Nation of Islam told oppressed African Americans that Jews were their primary exploiters, both in slavery and in urban poverty.

The economic roots of such scapegoating are still clear today, as when Right-wing pundits blame George Soros for the 2008 economic collapse, or MAGA conspiracy theorists tap into populist rage against decades of deindustrialization, job loss, and an out-of-control finance sector.1 But, as we can see from culture war campaigns that blame “cultural Marxists” for undermining traditional gender norms, conspiracy theories about blood drinking pedophiles rigging the election, or calls by advocates of race war to stop Soros-funded caravans they imagine storming the border, antisemitism’s causes are not simply economic.2 They tap into perceived threats to race and gender hierarchies, as well as xenophobia, deep-seated Christian supremacist tropes, widespread social alienation, and more.

Nearly 100 years after Trachtenberg wrote his essay, antisemitism retains many of its traditional particularities: The same hoary Christian tropes of Jewish malfeasance and demonic otherness circulate in church pews on Sundays, on social media, and in public discourse. Antisemitism remains a “social symptom” of a broader breakdown, and, as such, its manifestations often show up in attacks on other groups, not only Jews. Antisemitic conspiracy theories have led to attacks by insurrectionists on the Capitol, by vigilantes against Black Lives Matter protesters, Christian nationalists mobbing Drag Queen Story Hour and Pride events, and white nationalists committing mass shootings against Black and immigrant communities.

The conclusions Trachtenberg drew in his era of crisis remain true for our own: All non-Jewish marginalized groups, and anyone who believes in multiracial democracy, have a direct stake in fighting antisemitism. By the same token, Jews have a direct stake in fighting for justice and equality for all marginalized groups (groups of which many Jews are also members) and for democracy itself. Nothing short of a “revolutionary revamping of our social system,” as Trachtenberg put it, can win us the world we all need to thrive.

At the same time, some things have changed between his day and our own. Trachtenberg observed that fascist movements in his era peddled antisemitism as the “first line of offense in [their] war upon human rights.” He concluded that other groups endangered by fascism’s rise must realize that “to protect themselves they must protect the Jew first.”

Watching the dominant discourse today about antisemitism, one sees a dizzying inversion of Trachtenberg’s vision. Authoritarian movements themselves have claimed the mantle of fighting antisemitism. Nationalists from Donald Trump and GOP House Speaker Mike Johnson to Hungary’s Viktor Orban and Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu understand the strategic value of the idea that “to protect themselves they must protect the Jew first,” yet most Jews, to them, are primarily symbols or tools. Their real enthusiasm is for supporting the policies of the Israeli radical Right.

Thus, the fight for “Jews” has become a central plank in the authoritarian agenda. Even while they peddle antisemitism, these Right leaders pose as the greatest friends Jews have ever had. MAGA politicians like Marjorie Taylor Greene rail against “Rothschild space lasers” one moment and smear Jewish-led justice organizations as antisemitic the next. In a single breath, Christian Zionist leaders like Sean Feucht announce rallies ostensibly to protect Jewish students, while pining for the day of Rapture, when Jews and other non-believers will burn in hellfire.3

Trachtenberg advised Jews to utilize “the legislatures, the law-courts, the boycotts, [and] a relentless propaganda” to fight antisemitism. Today authoritarian forces, manipulating legitimate fears amidst rising antisemitism, seize upon efforts to enshrine the controversial International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism into law, knowing it will ease the way for wider restrictions on dissenting speech.4 They harass universities with frivolous complaints designed to pressure administrators to restrict academic freedom5 and employ right-wing media to condition millions of readers and viewers to see Muslims and progressives as terrorists and fifth-columnists — worthy of criminalization, deportation, and political violence. Democratic leaders or Jewish institutions joining in these efforts unwittingly strengthen anti-democratic forces that threaten Jews.6

In the years when Trachtenberg wrote “Stop Fascism: Preserve Democracy,” Jewish defense groups such as the ADL seemed poised to be key players in grassroots anti-fascist organizing across American civil society — disrupting fascist organizations, chasing Nazis off the streets, and launching a vigorous defense of liberal democracy.

But as the threat of fascist movements gave way to the threat of American McCarthyism, and as significant numbers of American Jews were given entree into racial and class privilege, groups such as the ADL began to reflect a rightward arc. Where once Jewish communal institutions cooperated to monitor actively antisemitic factions in the American Right, the postwar years saw these groups embracing surveillance of progressives and advocating for causes that wore away at multiracial coalitions. In the 1950s, as the Right persecuted progressives and disproportionately targeted Jewish, LGBTQ, and Black activists in its McCarthyist witchhunt, the ADL and American Jewish Committee not only failed to defend Jews who were targeted; they opened their files to McCarthy’s government agencies and engaged in their own witchhunts against suspected communists in Jewish institutions. After the 1967 Six Day War, the ADL devoted increasing resources to opposing anti occupation activists in progressive and Arab-American communities. In 1978, the ADL, American Jewish Committee, and American Jewish Congress were among a minority filing Supreme Court briefs in opposition to affirmative action.7 While they cited the ignoble history of antisemitic quotas to make their case, a deeper unease lurked: a sense that in areas of opportunity such as education, “more Blacks must necessarily result in fewer Jews.”8

Today, as major Jewish communal leaders invite notorious antisemites to share the stage at the March for Israel, call for the National Guard to crack down on students protesting for Palestinian rights, and honor Trump’s son-in-law while telling Jewish audiences, “I really don’t care how you vote,” the consequences of this pivot are glaring.9 Trachtenberg would have found it unimaginable, as he wrote in the shadow of Hitler, that nearly a century later, major Jewish leaders would openly ally with authoritarians in the name of fighting antisemitism.

…

Fighting fascism and antisemitism still requires building “a true ‘united front’” of marginalized groups “on a broad basis of defense of American liberties,” as Trachtenberg put it. But today’s climate complicates the work of coalition-building in ways he could scarcely have anticipated, and not only because major Jewish organizations have driven wedges between Jews and the other marginalized groups and social movements who could be our allies. It’s also complicated because Jews feel real reason to distrust some of those potential allies.

The anxieties that many Jews already felt about antisemitic currents within parts of the Left, and elsewhere in society, have become more pointed since October 7. Amidst widespread protest, instances of unaddressed antisemitic conspiracism, disregard for the humanity of Israeli Jews, and Manichean binary thinking have drawn headlines and condemnation. Chasms have deepened not only between Jews and potential allies, but also within the kinds of broad liberal-left pro democracy coalitions that Trachtenberg prescribes. We know that as these coalitions are divided, the likelihood of major gains for authoritarians in the U.S. grows stronger. But the work of repair feels daunting. We don’t know where to begin, and it is easy to despair.

Yet the divisions between Jews and our potential allies are not as unshakeable as they might seem. Perhaps no divisive tactic has been so consistent as attempts to paint non-Jewish progressive women of color as our enemies — even as antisemitism from white male leaders of the Right passes without remark. The case of Tamika Mallory offers a revealing example of how mutable such divisions really are. In 2018, Mallory, a leader of the Women’s March, drew widespread criticism after it was revealed she had attended an event led by Louis Farrakhan, the antisemitic and anti-LGBTQ leader of the Nation of Islam.10

The resulting public outcry provoked sharp divisions among supporters of the Women’s March — a major gain for MAGA. But Mallory had pre-existing, mutually committed relationships with Jewish activists. At the peak of crisis, these relationships made a difference. During a time when she faced consistently racist public attacks, Mallory had to discern valid critiques of antisemitism from bad-faith smears. Through in-depth conversations with fellow activist Sophie Ellman-Golan and others, Mallory deepened her own thinking about the need to fight antisemitism, and the march organizers rethought how to include Jewish women in the march.11

A year later, Mallory spoke to The Breakfast Club, an influential radio show for audiences of color. “[Antisemitism is] a real, serious problem,” she said. “It’s one that Black folks particularly need to pay attention to — because there are forces that want to be able to use anti-Black racism and antisemitism within the Jewish and Black communities to keep us apart. Because God forbid we ever pooled our power together and really, really started working together.”12

…

Even as they move further into the territory of the Right, mainstream Jewish defense organizations continue to use the “go and teach” method that Trachtenberg and others advised. Yet is this method working? Rather than responding to the rise in Palestine solidarity movements with a full-court-press of hot-pink JewBelong billboards, billionaire-funded Super Bowl ads, and legislative campaigns to restrict speech, what would happen if our institutional leaders paused to “go and learn” and “go and act”? What would happen if we approached marginalized groups and justice movements with openness and curiosity, asking questions like: What are the actual demands that student protesters are making, so often mischaracterized in the media? Why do marginalized groups see their own struggles reflected in the Palestinian demand for dignity, justice, and freedom? What does it feel like for them, when those in power smear their activism as antisemitic in order to shut it down?

Political education and awareness-raising around antisemitism remains vital. But unless it is grounded in a meaningful, consistent commitment to collective liberation — to building a world where all forms of oppression are defeated, and every group can be safe and thrive — it doesn’t meet what this moment requires, and it is unlikely to go very far.

Antisemitism is not a “disease,” an “epidemic,” a malaria-infested swamp, or some other force of nature to be tamed, quarantined, or immunized against, as Trachtenberg often describes and as many Jewish leaders today repeat.13 Rather, like any form of oppression, it is a creation of all-too-human hands, built and designed for all-too-human purposes, that can be defeated through human collective action. Rather than approaching the fight against antisemitism as technocrats, scientists, or social engineers, we should approach it as movement-builders: sleeves rolled to our elbows, ready to put in the patient work — alongside our partners — of transforming society, one conversation, organizing campaign, collective action at a time.

This approach recognizes that our liberation is fundamentally bound up with that of all other oppressed people, and it’s an approach I think Trachtenberg would agree with. In a time of crisis such as this, when stopping fascism within the U.S. is even more urgent than it was at the time of Trachtenberg’s writing, and strengthening relationships across difference is more complicated, it can feel difficult to pause and envision such an approach. But then, as now, it remains the only way forward.

NOTES

1 In 2010, two years after the worst financial crash since the Great Depression roiled the world economy, conservative pundit Glenn Beck debuted his Fox Television series “George Soros: The Puppet Master,” claiming that the liberal Jewish f inancier engineered the “crisis collapsing our economy” to institute “one world government.” A few years later, the closing ad of Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign, broadcast to millions of homes just days before the November 2016 election, railed against the “global power structure” that has “robbed our working class, stripped our country of its wealth and put that money into the pockets of a handful of large corporations, and political entities,” while flashing the faces of Soros and other Jewish financial leaders across the screen. “Glenn Beck’s Anti-Semitic Attack on George Soros,” Michelle Goldberg, (The Daily Beast, November 10, 2010) thedailybeast.com/glenn-becks-anti-semitic-attack-on-george-soros; “Trump Rolls Out Anti-Semitic Closing Ad,” Josh Marshall, (Talking Points Memo, November 6, 2016) talkingpointsmemo.com/edblog/trump-rolls-out-anti-semitic-closing-ad.

2 “Antisemitism & Misogyny: Overlap and Interplay,” David Lawrence et al, (London: Hope Not Hate and Antisemitism Policy Trust, September 2021); “Nearly Half of QAnon Followers Believe Jews Plotting to Rule the World,” Ewan Palmer, (Newsweek, June 28, 2021). https://www.newsweek.com/qanon antisemitism-morning-consult-survey-1604752; “Taking Aim at Multiracial Democracy: Antisemitism, White Nationalism, and Anti-Immigrant Racism in the Era of Trump,” Ben Lorber, (Political Research Associates, October 22, 2019) https://politicalresearch.org/2019/10/22/taking-aim-multiracial democracy.

3 “On last night’s livestream, Christian nationalist organizers of today’s ‘United for Israel’ march at Columbia explained that they’re actually excited about rising antisemitism: it’s a sign the End Times is near & Jews will convert to Christianity. Rally leader Sean Feucht:,” Ben Lorber (@BenLorber8), (Twitter, April 25, 2024).

4 The IHRA definition was formulated in the early 2000s as a non-legislative tool to assist in identifying antisemitism, but today, widespread campaigns urge governmental bodies and other institutions to adopt it into law. See “I drafted the IHRA definition. Rightwing Jews are weaponizing it,” Kenneth Stern, (The Guardian, Dec. 13, 2019) https://www.theguardian.com/ commentisfree/2019/dec/13/antisemitism-executive-order-trump-chilling-effect, and “Explainer: Arguments Against the IHRA Definition,” Diaspora Alliance, (November 2023) https://diasporaalliance.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/ IHRA-Explainer-and-Messaging.pdf.

5 “Once a Last Resort, Title VI Antisemitism Complaints Are Now the ‘Wild West’ for Jews on Campus,” Andrew Lapin, (Jewish Telegraphic Agency, February 29, 2024) https://www.jta.org/2024/02/29/united-states/once-a-last-resort-title-vi-antisemitism-complaints-are-now-the-wild-west-for-jews-on-campus.

6 “Pelosi Faces Criticism for Suggesting Some Pro-Palestinian Protesters Are Connected to Russia,” Aileen Graef, (CNN, January 8, 2024) https://www.cnn.com/2024/01/28/politics/pelosi-criticism-palestinian-gaza protests-russia; “Jewish groups push Congress to support IHRA definition of antisemitism,” Marc Rod, Jewish Insider, February 22, 2024, https://jewishinsider.com/2024/02/jewish-groups-ihra-definition-congress antisemitism-nexus/.

7 “The American Jewish Affirmative Action About-Face,” Jacob Scheer, (Tablet, July 31, 2018) https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/the-american jewish-affirmative-action-about-face.

8 Prof. Robert Langbaum, quoted in “Strangers in the Land: Blacks, Jews, Post Holocaust America,” Eric Sundquist, (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2009), 77.

9 “ADL Honors Jared Kushner at Annual Summit, Despite Pushback from Some Groups,” Luke Tress, (Times of Israel, March 7, 2024) timesofisrael.com/adl honors-jared-kushner-at-annual-summit-despite-pushback-from-some-groups/; “ADL Chief Backs Campus Crackdowns. As a Student, He Stood Up for Free Speech — Even by Antisemites,” Andrew Silverstein, (Forward, April 27, 2024) https://forward.com/news/607054/adl-jonathan-greenblatt-campus-protests columbia/; “Liberal Jewish Groups Lament DC Rally’s Rightward Bent, Say Progressives Pushed Away,” Charlie Summers, (Times of Israel, November 17, 2023) www.timesofisrael.com/liberal-jewish-groups-lament-dc-rallys-rightward bent-say-progressives-pushed-away/.

10 Mallory differed significantly with Farrakhan’s philosophy but was committed to engaging with groups who played significant roles in Black communal life, and was particularly appreciative of NOI’s work against gun violence, which had impacted her family. “Tamika Mallory Speaks: ‘Wherever My People Are Is Where I Must Be,’” (NewsOne, March 7, 2018) https://newsone.com/3779389/ tamika-mallory-saviours-day/.

11 “Women’s March Jewish Outreach Director: ‘Anti-Semitism Can Be Unlearned,’” Mairav Zonszein, (+972 Magazine, January 29, 2019) https:// www.972mag.com/womens-march-jewish-outreach-director-anti-semitism-can unlearned-addressed/. The next year, a powerful contingent of Jewish women of color led the Women’s March, alongside Mallory and other organizers. “9 Jewish Women of Color on Why They’re Going to the Women’s March,” Nylah Burton, (Hey Alma, January 17, 2019) https://www.heyalma.com/9-jewish-women-of color-on-why-theyre-going-to-the-womens-march/.

12 “Tamika Mallory on Her Appearance on The View, the Women’s March & Tangible Change Within Communities,” (Breakfast Club Power 105.1 FM, video, January 16, 2019) 11:20–11:45.

13 “Messaging Training: How to Fight Anti-Semitism in Solidarity,” Sharon Goldtzvik and Ginna Green, (Pittsburgh, PA: presentation, Netroots Nation, August 18, 2022).

BEN LORBER (he/him) is a writer, researcher, and educator. As Senior Research Analyst at Political Research Associates, a movement-facing think tank, Lorber helps progressives understand and fight antisemitism and white nationalism. Lorber is co author, with Shane Burley, of “Safety Through Solidarity: A Radical Guide to Fighting Antisemitism” (2024).