Martin Luther King, whose birthday we remember and celebrate this week, confirmed what Pharaoh’s behavior already taught us: God helps each of us become who we are determined to become.

Amongst the most obvious differences between the modern giant of social justice and the ancient Egyptian ruler is that MLK had, in his own words, an “inner urge to serve humanity,” while Pharaoh not only served himself, he acted as if he was a god incarnate. As is the reality for much of life, the paths taken by each were dramatically different, but the dynamic that led each to become who they were is strikingly similar.

A cursory reading of the narrative that began in last week’s portion, Vaera, and continues into this week’s, Bo, might leave the reader with the impression that Pharaoh was nothing more than a tool of the eternal God, stripped of his own free will. His heart, it might appear, was repeatedly hardened by God, so that God would have a pretext by which to continue to rain plagues down upon Egypt.

In fact, even in translation, a closer reading yields a different and more valuable understanding. There are different expressions used to describe Pharaoh’s determination, which translate, more literally, as his heart was made heavy or dense (stubborn), and alternatively, that his heart was strengthened (stiffened). After each of the first five plagues, Pharaoh became more stubborn, strengthened his own resolve. As God brought progressively more damaging plagues upon Egypt, Pharaoh stubbornly continued to strengthen his own resolve not to give in – not because of his belief in the righteousness of his cause, but his unwillingness to accept that there was one more powerful than he. It was only after the sixth plague, boils, that God strengthened Pharaoh’s heart – but that is all God did. God never took away Pharaoh’s free will. The plagues affected not only him, but all of the Egyptians. They became convinced early on of the need to change course, but not Pharaoh. Sadly, he acted not out of conviction, or a sense of righteousness, but out of stubbornness and hard-heartedness.

The message is clear: just as the most righteous of human beings, even the most evil of human beings has free will, and God helps each of us become who we are determined to be, strengthening our resolve to act in the ways we choose to act, reinforcing our capacity to become who we are committed to become.

There could hardly be a more dramatic contrast to Pharaoh in deed and intention than Dr. King, but it is striking how he, too, given free will, became more and more resolved to become the person that he became. The challenges that he faced affected him more directly than the ones that Pharaoh experienced: consider, for example, the brutal police responses to both Birmingham and Selma. Like Pharaoh, King persevered in the face of the “plagues” that came his way, and was undeterred. But only the most jaded critic would describe him as stubborn. He was, in his truly righteous activist efforts, the model of conviction. He did all he did out of his conviction that there was a power greater than himself that called on him to do so. Pharaoh, to the contrary, was committed to and interested in only his own power, and what was beneficial to him, denying the existence of a power greater than himself. Therein lies the distinction between conviction and stubbornness – and at its core, the distinction between Dr. King and Pharaoh.

We never hear from Pharaoh again after the last of the plagues, but the name he made for himself, and his legacy of self-glorification, reckless disregard for his own people, and oppression of the Israelites are with us after thousands of years. May it be that even more than the name he made for himself, Dr. King’s legacy similarly lives on.

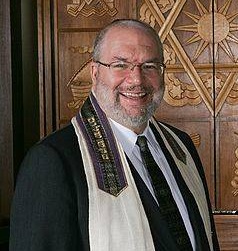

Howard L. Jaffe is the senior rabbi of Temple Isaiah in Lexington, MA, and is the current president of the Massachusetts Board of Rabbis.