This week’s Parashah, Miketz, contains the well known story of Joseph interpreting Pharaoh’s dreams about the seven fat cows being devoured by the seven skinny cows and the seven healthy sheaves of wheat being displaced by the seven sickly sheaves.

Joseph, brought out of his prison cell to interpret the dreams, goes farther and advises Pharaoh on how Egypt can survive the coming famine: “Now, therefore let Pharaoh look for a man discerning and wise, and set him over the land of Egypt… and let him appoint overseers over the land and take up the fifth part of the land of Egypt in the seven years of plenty… And the food shall be a store to the land against the seven years of famine… that the land perish not through the famine.” (Gen. 41:31-36)

Joseph’s words contain an understanding of what it means to be hungry. In his life he has known both plenty and deprivation. His life begins as the son and grandson of wealthy men. He is sold into slavery, becomes the head of Potiphar’s household, and until this moment he has languished in prison. He understands both what it means to have food and what it feels like to hunger for a most basic meal. His advice to Pharaoh is a call to ensure the survival of all Egyptians, not just the rich.

While not phrased this way, in this moment Joseph calls upon Pharaoh to remember and understand the heart of all people. Sadly, as time passes, Joseph forgets he has lived with food uncertainty while languishing in prison.

In her commentary New Studies In Bereshit: Genesis, Nehama Leibowitz writes: “According to Rashi, the lean cows’ devouring of the fat ones, without any improvement in their state, expresses the eating in terms of the destruction of the object eaten, and not of the beneficial effect on the eater. Accordingly, the eating and swallowing of the fat cows by the lean ones has to be taken as symbolising the forgetting of the period of plenty in the days of famine.”

Joseph, however, does not forget the time of plenty. Rather, while the land starves, he works to ensure that he, his family, the Egyptian priesthood, and Pharaoh will always have plenty. In next week’s Parashah, Vayigash, we read (Chapter 47:12 -26) that Joseph first charges for the food and seed that he took from the people in the seven years of plenty; then, when they are out of money, he takes their livestock and finally their land, making them at best landless serfs to Pharaoh and Joseph.

The parallel to our own times is sadly obvious. Instead of the Joseph who calls upon Pharaoh to remember and understand the heart of the people, we live in the society of the later Joseph who sets up a system that ensures some will always have plenty because of the labor of those who eke by.

Which Joseph do we want to be?

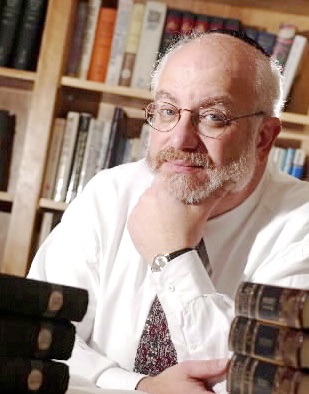

Rabbi Rosenfeld’s portrayal of the two Josephs also appears in T’ruah’s text study about human rights and climate change.

Harry Rosenfeld is the rabbi of Congregation Albert in Albuquerque, NM. He has previously served congregations in Memphis, TN, Anchorage, AK, and Buffalo, NY.