The following is an excerpt from “Fragments III: Democracy, “ a journal from T’ruah.

Evaluating the state of American democracy in 2024 is an exercise in dialectics. Dialectical thinking — developed, like democracy itself, by the Ancient Greeks — is an approach to analysis that considers multiple perspectives as a way to reconcile seemingly contrasting or contradictory information.[1] It’s how we, the co-authors, work our way through our shared belief that democracy is both the fairest, most inherently just system of governance currently available, and that it’s also capable of producing and tolerating great injustice. That democracy can fail to deliver in the short term while providing the best chance at success in the long run. That it can be worth fighting for even while it disappoints us.

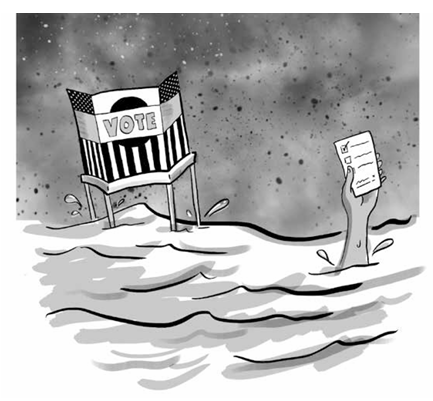

It can be an uneasy marriage of beliefs, but it’s one we feel confident stands up to scrutiny — and American democracy is weathering serious scrutiny. Only three in 10 Americans think democracy is functioning well, according to a recent study. Just over half grade democracy as “poorly functioning” overall.[2] Even more stark, just over 20 percent of Americans report feeling that violence may be necessary to get the country back on track.[3,4]

Many feel democracy is not delivering on its promises, or not delivering fast enough. Economic stagnation (real and perceived) has plagued the U.S. since long before the Great Recession of 2007.[5] Abundant evidence shows that Black Americans do not benefit from equal protection under the law; they face harsher punishments, longer prison sentences, and more frequent violence at the hands of law enforcement than white citizens. Meanwhile, large groups of Americans — many without college degrees and/or in rural areas — have grown increasingly resentful of a dominant culture that they feel disregards traditional values and local customs. [6]

At the heart of this matter — buried underneath layers of political theater, toxic polarization, purity politics, and unhelpful algorithms — is a basic question: Is our current system of self-governance capable of building the society we want to live in? We argue that the answer is yes — indeed, we believe it is our best shot — but only if we are willing to confront and understand its origins, aspirations, and limitations. In essence, we must be willing to accept that democracy does not equal progressivism, though it is a way to pursue it.

Origins: The Evolution of Liberal Democracy

What is American democracy, and where did it come from? Like most political systems, democracy comes in many shapes and sizes. Born in Ancient Greece and nurtured in Enlightenment Europe, our uniquely American manifestation is built on the principles of liberal democracy. Liberal democracy’s core elements, as originally defined in the 18th century, include free and fair elections, constitutionally enforced limits on government power, free markets, free speech, a definition of citizenship that included the middle class, and equal protection under the law.

These principles were, however, just glimmers of possibility when “democracy” emerged in Athens as a system of local governance between the sixth and fourth centuries BCE.[7] The Athenian system comprised a complex and interdependent set of institutions for self governance among free, male inhabitants (about 10-20 percent of the population).[8] Participation among these citizens was quite high, though non-citizens including women and enslaved people had few rights. This model for self-governance evolved into something new in Enlightenment-era Europe. While still limiting democratic rights to free, white, male property-owners, European advocates of democracy brought the Athenian model into dialogue with the newly defined principles of Classical Liberalism.

Classical Liberalism focused on maximizing the freedom of individuals in social, economic, and political life.[9] Its resistance to any form of coercion offered a conceptual alternative to the tyranny and arbitrary violence of monarchies and aristocracies that claimed to rule by divine right, or imposed rule by force. From these ideals grew the vision of “liberal” democracy, which enshrines protections for individuals through elected, representative governments that are meant to act in the people’s best interest according to codified laws and principles, rather than through the use of force. Liberal democracy also espouses a commitment to a robust marketplace of ideas.[10] Crucially, liberalism recognizes that, in a pluralistic system, the freedoms of some will conflict with the freedoms of others. To account for this, liberal democracy maintains structures to support and defend ideological pluralism in which individuals — and the institutions they form — can safely advocate for their own interests in public life. Essentially, any liberal democracy has to tolerate the discomfort and disagreement that diversity produces, and guarantee the orderly and nonviolent resolution of conflict.

It was within this revolutionary intellectual framework that the 13 American colonies began to contemplate the country that they would become. The future United States was, even at that time, more ethnically, religiously, and geographically expansive than its European antecedents. It was the only place during this time where both a liberal democracy and national identity were being built from scratch. It was, in many ways, James Madison who widened the scope of American democratic possibilities, arguing with brilliance and hubris that liberal democracy could — through robust dialogue among regional factions and levels of government — agree upon a binding written constitution to govern all 13 colonies together as one nation.[11]

It should also be noted that the foundation of religious pluralism that undergirds American liberal democracy has had a particular impact on American Jews. Although antisemitism remains present, and many Jews of different backgrounds still face other oppressions, including racism, sexism, homophobia, and ableism, American democracy has traditionally produced an unusual degree of safety and stability for Jews — particularly in comparison to what Jews had historically experienced in Europe and elsewhere. Credit for this usually begins with the development of the “church-state separation” principle, pioneered by Roger Williams in the founding of Rhode Island. Eventually carried forward by Thomas Jefferson, this principle declared governments and leaders fallible, rather than representations of perfect godliness on Earth, and thus accountable to the people they serve. It also ensured the United States did not elect Christianity as its national religion, which would have carried with it legal justification at the federal level for the marginalization of non-Christians.

Policies and statements like George Washington’s “Letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island” (1790), the Bill of Rights (1791), and the Treaty of Tripoli (1796) were part of a radical paradigm shift concerning the treatment and inclusion of Jews in the West. They declared an intent to offer equal treatment across religions, something unheard of in Europe at the time. In this way, Jewish American history is inextricably linked to the grand experiment of turning the ideas of liberal democracy into a lived reality.

Aspirations: The Unique (and Frustrating) Realities of Democratic Governance

The result of this ongoing experiment is our current system, a vast and imperfect amalgamation of direct and representative democratic institutions that have, at various times, pushed us forward and backward in our pursuit of freedom and justice for all. For example, direct democracy, best typified in America by state-level ballot initiatives, brought both California’s 2008 ban on same-sex marriage[12] and the recent defeat in Kansas of a constitutional amendment which would have outlawed access to abortion.[13] Whether you agree with either of these outcomes, they represented the will of the people in those times and places.[14] The alternative, historically speaking, has been systems of governance in which a very few (technocrats, hereditary monarchs, the ultra-wealthy, the best armed) have made the rules.

Dr. Hahrie Han of Johns Hopkins University argues that a healthy democracy is one in which we are willing to trade certainty about outcomes for certainty about process, one in which how we get somewhere is more important than where we’re going.[15] She often utilizes a comparison between American and Russian elections. In 21st century autocratic Russia, we can be relatively certain Vladimir Putin will win the presidency; we just can’t be sure how he’ll do it. In contrast, in America — as we feel acutely right now — we don’t know who will win any particular election, but we do have a transparent (if not always equitable) system of state and federal laws that govern how it will be adjudicated.[16]

This is the aspiration of liberal democracy: a shared, transparent, and increasingly equitable methodology to insulate us from the whims of capricious rulers or fickle majorities; one that ensures that democratic expectations are shared and enforced across communities and time periods; and one that contains within it mechanisms for correction when it goes awry. Liberal democracy is an investment in a more just and inclusive process to pursue a more just and inclusive society.

While our progress has not been linear, it is undeniable that America is demonstrably freer and more equal now than it was at its founding. The legal machinery of our liberal democracy has enabled Americans to challenge our society’s contradictions and injustices. The manifestos that emerge from moments of change in America[17] show how citizens continue to push our democracy forward. As a result, over the last century, state and federal laws have expanded the rights of citizenship to widening circles of Americans across lines of gender, race, religion, and national origin. American liberal democracy has at various times produced a social safety net; the right to unionize; the right to be free of discrimination in housing, education, and employment; and a whole suite of environmental protections.

There have been and will continue to be profoundly painful setbacks — for example, the Supreme Court decisions in Korematsu v. United States, which upheld the constitutionality of Japanese internment during World War II, and Shelby v. Holder, which effectively gutted the enforcement provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But there have been bright spots, too, and they are worth remembering. Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan’s lone 1896 dissent in Plessy vs. Ferguson planted a seed that more than 60 years later was invoked to overturn “separate but equal” in Brown vs. Board of Education.[18] Article VI of the US Constitution, which prohibited religious tests for those seeking elected federal office, was radically inclusive for its time and made way for legislation like the “Jew Bill” of 1826, which granted Jews the right to hold public office in Maryland, the last state where it was prohibited. The 19th amendment granted women the right to vote in 1920, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 made this right more tangible, especially to Black women. The 2015 SCOTUS decision in Obergefell v. Hodges confirmed a constitutional right to same-sex marriage. This history represents the best of liberal democracy: the dogged pursuit of justice through a clear and responsive system, the engagement of individual Americans and civil society organizations, and the refusal to let the bigotries of the past dictate the future.[19]

Belief systems are not fixed. Times and minds change, and when they do, conflict arises. It is in periods of conflict that liberal democracy offers and aspires to a demonstrably better approach than other forms of governance. Indeed, 19th century American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce reminds us of the options nations resort to in the absence of democracy, noting that “when complete agreement could not otherwise be reached, a general massacre of all who have not thought in a certain way has proved a very effective means of settling opinion in a country.”

Stoking this kind of political violence is a classic tool of authoritarians, as “such outbreaks can offer political cover for restrictions on civil liberties or the expansion of coercive security measures.”[20] Contrastingly, citizens of healthy democracies (versus those under other forms of government) are least likely to report believing that “crime, violence, or terrorism is the greatest risk to their safety” — and least likely, according to data analyzed at the national level, to experience violence.[21] This does not mean crime and violence do not exist, or that certain populations do not experience them more acutely. We know, for example, that American Indian and Alaskan Natives experience astronomically higher rates of violence than the average American.[22] What it does mean is that compared to other systems of governance, democracy has shown itself the most effective at regulating monopolies on force and keeping its citizens safe.

Limitations: Democracy Alone Is Not Enough

Democracy is not an all-or-nothing state of being, something we have or don’t have. It’s a contingent process made up of rules, norms, institutions, and actors, all in dynamic relationship with one another. How these elements interact determines the relative health and vitality of our democracy at any particular moment. Limitations abound; first and most important, that actors on all sides of the political divide agree to play by the rules and respect the norms.[23]

Just, democratic processes can lead to unjust outcomes. Our challenge is to remember that legitimacy and accountability for American democracy comes from us — the people. Our choice of orientation at this moment is not limited to the binary of “it’s broken beyond repair” and “it’s perfect and above reproach.” Patriotism, not a popular word among political liberals,[24] does not mean unquestioning acceptance of eroding institutions. Indeed, it means the opposite: active engagement to build, iterate, evolve, and rebuild systems and institutions that do not yet meet our standards for equity, justice, and freedom. It is that active engagement that enables us to take desperately needed steps, such as correcting for gerrymandering’s devastating influence on equal representation, so that all eligible citizens, regardless of zip code or race, have equal access to the franchise. Such corrections are only possible with more investment in our democracy, not less.

Conclusion

The ability to hold contradictions is a vital skill for assessing the success of American democracy, as is a clear-eyed understanding of our history. Self-governance does not guarantee justice or a linear march toward progressivism. It can’t. Not without a homogeneous population perfectly aligned on a shared vision for a progressive future. What it can do, if properly invested in and defended by its citizens, is guarantee a process to advocate for and realize that world in steps, sometimes large and sometimes small. Our task as those citizens is not to ignore or excuse the moments we have failed (or when the system has failed us), but to approach these failures as a call to action to work harder to realize a more perfect union. It’s up to us.

NOTES

1“Dialectical thinking: A generative approach to critical/creative thinking.” Manzo, Anthony V., Garber, K. and Warm, J. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Reading Conference, San Antonio, TX, 1992.

2“Most Say Democracy Is Important for the U.S. Identity, but Few Think It Is Functioning Well,” (AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, March 2024) https://apnorc.org/projects/most-say-democracy-is -important-for-the-u-s-identity-but few-think-it-is-functioning-well/

3“Biden Plus 2 Percentage Points Over Trump, but Conventional Wisdom Comes Into Question,” (Marist Poll, NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist National Poll, April 3, 2024) maristpoll.marist.edu/polls/april-2024- presidential-election

4 Importantly, such views are not limited to the political right. From Rachel Kleinfeld, “The problem for democracy on the left is not those who report high polarization (those individuals tend to be active and politically engaged in a positive way for democracy), but a very small but vocal group that the international anti-polarization organization, More in Common, terms ‘activist mavericks.’ These individuals are younger and wealthier than average Americans and more often male. They are far-left in their ideology, but they dislike the Democratic Party and so are not partisan (though they may be effectively polarized and hate Republicans). They claim to be very strongly pro-democratic. But they do not believe America has achieved democracy, and so they are willing to support political violence to achieve greater racial and democratic representation. 60 percent support property crime (versus 6 percent of Americans overall), and 28 percent support violence against people (versus 4 percent of the population overall).” “Polarization, Democracy, and Political Violence in the United States: What the Research Says,” Kleinfeld, Rachel, (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 5, 2023) https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/09/polarization-democracy-and-political-violence-in-the-united-states-what-the-research says?lang=en

5“The Populist Challenge to Liberal Democracy,” Galston, William A., (Brookings, April 17, 2018) www.brookings.edu/articles/the-populist-challenge-to-liberal democracy.

6 ibid.

7“Origins of Democracy in Ancient Greece,” Raaflaub, Kurt A., et al., (2007) p. 10-12.

8 ibid.

9 For an excellent introduction to Classical Liberalism, see “Classical Liberalism: A Primer,” Eamonn Butler, (Institute of Economic Affairs, July 16, 2015) iea.org. uk/publications/research/classical-liberalism-a-primer.

10 ibid.

11 “American Creation,” Ellis, Joseph P., (Vintage Books, 2008) p. 105-106.

12 “California Proposition 8, Same-Sex Marriage Ban Initiative (2008),” (Ballotpedia) ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_8,_Same-Sex_Marriage_ Ban_Initiative_(2008). Note that Proposition 8 is not currently enforced but remains on the books in California.

13 “Voters in Kansas Decide to Keep Abortion Legal in the State, Rejecting an Amendment,” Lysen, Dylan, (NPR, August 3, 2022) https://www.npr.org/ sections/2022-live-primary-election-race-results/2022/08/02/1115317596/kansas voters-abortion-legal-reject-constitutional-amendment

14 The right to vote and access to the polls have been contested throughout American history, and no election perfectly represents the will of all of the people. But the promise of democracy is that over the long arc of history, elections become ever more free, fair, safe, and accessible.

15 “Cultivating the Practice of Democracy,” Han, Hahrie (April 2023) youtube/TA1ZzBH5NSk.

16 It is worth noting in this moment that, according to a 2024 report from Voting Rights Lab titled “The Shapeshifting Threat of Election Interference,” “for millions of voters across the country, this will be the most accessible election they have ever experienced.” Indeed, since 2020, significantly more legislation expanding access to voting and election infrastructure has been enacted than restricts access or impedes election administration. It should also be noted that the lived experience of these facts will vary tremendously by state, economic status, immigration status, and race.

17 Take, for example, Thoreau’s “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience,” the Seneca Falls Convention, the Port Huron Statement, Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” and Mario Savio declaiming for free speech on Sproul Plaza.

18 “Harlan’s Great Dissent,” Thompson, Charles, (Kentucky Humanities, vol. 1996, no. 1, 1996) https://louisville.edu/law/library/special-collections/the-john marshall-harlan-collection/harlans-great-dissent

19 “Maryland’s ‘Jew Bill,’” Eitches, Edward, (American Jewish Historical Quarterly (1961-1978), vol. September 1970 to June 1971, no. 60: 1-4) p. 258–76, msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/013400/013489/pdf/ajhq_2.pdf.

20 “The Authoritarian Playbook,” Dresden, Jennifer, et al., (Protect Democracy, June 15, 2022).

21 “Global Peace Index 2021: Measuring Peace in a Complex World,” (Sydney: Institute for Economics & Peace, June 2021) https://www.visionofhumanity.org/ global-perceptions-of-safety-risk-government-type/.

22 “Five Things About Violence Against American Indian and Alaska Native Women and Men,” (U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, May 2023) https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249815.pdf.

23 Examples of our political leaders failing to respect the norms and rules of our democracy include the refusal of Senator McConnell to call a confirmation vote on now-Attorney General Merrick Garland and the refusal to acknowledge legitimate defeat by either Former President Donald Trump or Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who, as recently as 2019, has dismissed Former President Trump as illegitimate.

24 “Civic Language Perceptions: How Civic Language Unites, Divides, & Motivates American Voters,” (PACE (Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement) and Citizen Data (2024). Civic Language Perceptions Project, National Surveys collected November 2021 and 2023) PACEfunders.org/Language.

SOFI HERSHER ANDORSKY (she/her) serves as Vice President of Strategy & Communications at A More Perfect Union. Sofi has previously worked for Twitter, the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, ignite Digital Strategy Group, and her own consulting firm, Grand View Strategies, which focuses on initiatives at the intersection of faith and civic life. Sofi is currently a Sinai and Synapses Fellow, a Wexner Field Fellow, and the Vice Chair of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty.

AARON DORFMAN (he/him) is Founder and Executive Director of A More Perfect Union. He has also served as President of Lippman Kanfer Foundation for Living Torah, Vice President for Programs at American Jewish World Service, and Director of Informal Education at Temple Isaiah of Contra Costa County. Aaron serves on the Advisory Board of the Safety Respect Equity Network and on the board of Policy Impact.

AARON DORFMAN (he/him) is Founder and Executive Director of A More Perfect Union. He has also served as President of Lippman Kanfer Foundation for Living Torah, Vice President for Programs at American Jewish World Service, and Director of Informal Education at Temple Isaiah of Contra Costa County. Aaron serves on the Advisory Board of the Safety Respect Equity Network and on the board of Policy Impact.