The following is an excerpt from “Fragments III: Democracy, “ a journal from T’ruah.

We are in the midst of a democratic crisis. Global freedom has declined for 18 years in a row,[1] largely driven by attacks on pluralism, armed conflict, and flawed elections. Here in the U.S., we have seen efforts to overturn elections, roll back access to voting, particularly for communities of color, and restrict the right to protest and to free speech.

This reality is dangerous for everyone — including for Jews, as antisemitism tends to rise in times of economic and political upheaval. Already, we have seen increased antisemitic violence and threats, driven both by the rise in white nationalist movements and by anger about the Israel-Hamas war.

For liberal Jews, it has become a principle of faith that Judaism supports democracy. Especially during election years, we see an outpouring of articles, speeches, and organizational pronouncements declaring democracy to be inherent to Judaism, and insisting that only democracy can ensure Jewish safety.

Inconveniently, neither Jewish text nor history precisely supports these assertions. Rather, the bulk of Jewish tradition seems to view monarchy as the ideal — or at least default — mode of government, since that was the most familiar form of government under which Jews lived for centuries. And while Jews certainly have been safest under governments with strong protections of civil liberties, democracy bears its own pitfalls, including the danger of populism, which has historically included the spread of antisemitic conspiracies and mob violence against Jews.

I, for one, am certainly not ready to throw democracy out the window. Rather, I echo Rabbi Chaim David HaLevy (1924-1998), the former Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv, who, when asked about democracy, responded,

“It is not the intention of this article to disparage democracy as the best form of government in our time, given the conditions of our lives, as it is clear that there is no better way than this… And, at the same time, [I intend] to describe by way of comparison with government according to the Torah the deficiencies of government built on the foundations of democracy. Even so, the conclusion is that in our time, there is no better alternative to democratic rule.” (Mekor Chayim 3:52)

Rather than ask a yes/no question — does Judaism support democracy? — I want to instead ask what principles Judaism offers us for how to build an ideal society, and how we can apply these principles in our fight for justice and freedom today.

Appointing a King: Mitzvah or Danger?

As the Israelites prepare to enter the Land of Israel, and for the first time to achieve sovereignty in their own land, the Torah offers a prediction and a caution about their likely future government:

If [Ki], after you have entered the land that THE ETERNAL your God has assigned to you, and taken possession of it and settled in it, you decide, “I will set a king over me, as do all the nations about me,” you shall be free to set a king over yourself, one chosen by THE ETERNAL your God. . . And he shall not have many wives, lest his heart go astray; nor shall he amass silver and gold to excess. When he is seated on his royal throne, he shall have a copy of this Teaching written for him on a scroll by the levitical priests. Let it remain with him and let him read in it all his life, so that he may learn to revere THE ETERNAL his God, to observe faithfully every word of this Teaching as well as these laws. Thus he will not act haughtily toward his fellows…. (Deuteronomy 17:14-20)

It’s predictable, the Torah suggests, that the people will desire the same form of government as other sovereign nations. But, as a nation recently freed from Pharaoh’s servitude should understand, the establishment of a monarchy carries risks of tyranny. The remedy for this risk is Torah. Only through constant reminders of his ultimate obligation to God will the king avoid these dangers.

Given that the Hebrew word ki can mean both “if” and “when,” monarchy can be read as either inevitable or optional. The rabbis of the Talmud, however, understand appointing a king to be one of the three mitzvot incumbent on the Jewish people when they enter the Land of Israel. (Sanhedrin 20b)

Certainly, the bulk of Jewish tradition assumes the presence of a monarchy. Despite the prophet Samuel’s dire predictions that a king will exploit them (I Samuel 8), and despite the series of kings who follow — some who take seriously their divinely appointed mission, and others who disobey God, amass wealth, enter into ill-conceived wars, and bring about catastrophe — the Talmud and most later canonical writings continue to insist on monarchy as the ideal form of government. In the Mishneh Torah, for example, Maimonides asserts that appointing a king must be the first mitzvah performed upon re-entering the land, lays out specific criteria for such kings, and then allows the king broad powers, even ones that sometimes override the letter of the law.

Nevertheless, some commentators take a more expansive view of the necessity of a king. Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (known as the Netziv, 1816-1893) writes,

It is not an absolute commandment to appoint a king, but rather optional. . . There are states that cannot stand a monarchy and there are states that without a king are like a ship without a captain. . . It is impossible to absolutely command the appointment of a king as long as the people do not consent to the yoke of a king as a result of seeing the states around them functioning more properly [with a king]. Only then is it a positive commandment for the Sanhedrin to appoint a king. (Comment on Deuteronomy 17:14)

The Spanish commentator Don Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508) looks to Venetian government, as he understood it, as a model of democratic rule and notes,

There can be among the people many leaders who gather and unite and agree upon one policy, and the leadership and the law can be according to them. . . we have seen many lands whose leadership is by temporary judges and governors who are chosen among them, and God the Sovereign is with them. (Comment on Deuteronomy 17:14)

Crucial both to the biblical text and to its various interpreters is the insistence that a government — whether a monarchy or some other form — must be dedicated to serving God and to the wellbeing of the people, and not to fulfilling the personal interests of the leaders. This basic principle opens space for a more expansive conversation about what a just society should look like, beyond the question of how leaders are chosen.

Democracy: More than Just Elections

The Torah’s assertion that human beings are creations “in the image of God” sits at the core of Jewish explorations of how to create a just society. Early rabbinic tradition offers a series of metaphors that describe human beings as reproductions, reflections, or extensions of God, with the obligations that accompany intelligence and free will, and with a claim to infinite worth. Legal and narrative conversations about how to establish a just society concretize this idea into laws and principles that aim to ensure the dignity of everyone.

While present-day conversations about democracy generally focus on elections and free speech, democracy also includes a much broader set of principles, including, per an enumeration by the UN Commission on Human Rights, “respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms,” “freedom of expression and opinion,” “the independence of the judiciary,” and “transparency and accountability in public administration.”[2]

Through a review of some key Talmudic texts, primarily from Seder Nezikin — the set of Talmudic tractates that address civil and criminal law and societal relations — I will consider if and how these principles show up in Talmudic conversations about how to establish a just society, and what these discussions might teach us today.

There’s a famous moment from Barack Obama’s 2012 presidential campaign that encapsulates a fundamental disagreement about the relationship between individual Americans and the broader society. In a speech, he declared,

If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen.

In response, the Romney campaign launched the slogan “we built that.” For believers in the myth of American rugged individualism, it’s each person for themselves. Those who succeed do so based only on their superior talents and determination, and those who suffer economically have only themselves to blame.

This brand of rugged individualism has no place in Jewish conceptions of a just society, which envision a community that is invested in the dignity and wellbeing of all its members, and that imposes responsibilities for the collective on every individual.

One Talmudic text presents a list of the basic elements that must be present in a city in order to be a fit residence for Torah scholars:

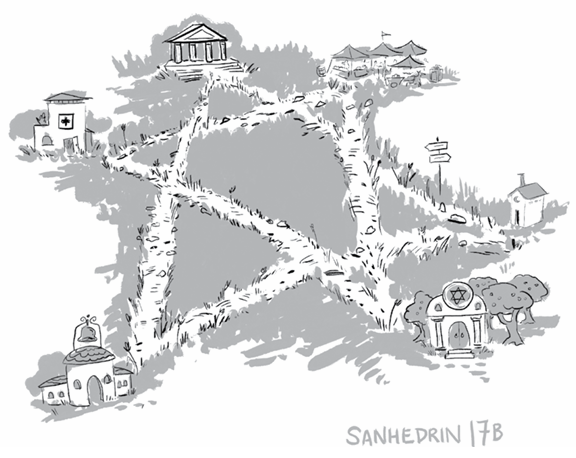

A Torah scholar is not permitted to reside in any city that does not have these 10 things: A court that has the authority to flog and punish transgressors; and a charity fund for which monies are collected by two people and distributed by three. And a synagogue; and a bathhouse; and a public bathroom; a doctor; and a bloodletter; and a scribe (and a butcher), and a teacher of young children. They said in the name of Rabbi Akiva: The city must also have varieties of fruit, because varieties of fruit illuminate the eyes. (Sanhedrin 17b)[3]

These elements fall roughly into four categories: Basic public health institutions (a bathhouse, a bathroom, a doctor, a bloodletter, and perhaps fruit); religious infrastructure (a synagogue, a school, a kosher butcher); a justice system (a court that can decide cases and mete out punishments and a scribe who can write documents); and a system for caring for the poorest members of society (a tzedakah fund).

We can understand this text as concerning itself only with the welfare of the (male) Torah scholar. Or we can read the text more broadly, as an assertion that there can be no Torah in a place that does not first commit itself to the physical, spiritual, and economic health of all of its residents.

This latter reading reflects the insistence within Jewish law on defining responsibilities toward others as religious precepts. It’s no accident that the first Torah portion following the revelation at Sinai delineates a series of laws concerning employer/employee relations, courts, and other civil matters. Nor is it surprising that Seder Nezikin, the collection of tractates primarily engaged with civil law, from which most of the texts in this essay come, is one of the more extensive of the six sections of the Talmud. Jewish law concerns itself not only with ritual practice, but also with how to build a just society. For scholars and anyone else, benefiting from communal resources requires assuming collective responsibilities, as the Talmud makes clear by laying out a schedule for when new residents must begin contributing to social safety net institutions such as the various tzedakah funds. (Bava Batra 8a)

Additionally, residents must contribute to communal infrastructure, including building defensive walls for the city. But how much should each person pay? The Talmudic rabbis don’t even consider the possibility of a flat tax. Instead, they offer two major possibilities: Residents should pay either according to wealth, or according to their proximity to the edge of the city, and therefore their vulnerability in case of attack.[4]

For most later commentators and legal authorities, it’s inconceivable that a poor person living close to the edge of the city, presumably a less desirable location because of the inherent danger, would pay more than a wealthy person living in the center of the city. Many later commentators therefore split the difference and rule that proximity to the wall becomes the determining factor only when household incomes are on par with each other.[5]

We could certainly imagine a different scenario — perhaps one more in line with the model of American individualism — in which the wealthy build high walls around their own property and decline to contribute to the safety of the whole. While individual homeowners, per the Talmud, certainly may erect their own walls, investing in one’s own protection does not allow one to abdicate their responsibility toward the collective. Even a gatehouse, the commentators conclude, may only be constructed around a group of homes if it allows those in need of tzedakah to enter.

Balancing the Needs of the Whole with the Dignity of the Individual

Much of Tractate Bava Batra concerns itself with the precise nature of the relationship among neighbors and between an individual and the broader society. For example, much ink is spilled considering a situation in which one’s own livelihood may damage another’s property. In general, a person cannot claim that because an activity physically takes place on their own property, they bear no responsibility for the impact on others. For instance, a tannery, which is notoriously smelly because of the use of urine as a softening agent, must be placed outside of the city (Chapter 2). The discussions of how to balance an individual’s right to their own property and livelihood with the rights of their neighbors and of residents of the city as a whole occupy much of the tractate.

As evidenced by these considerations, Jewish law may reject the model of rugged individualism, but it also does not seek to subsume the individual into the collective. If every person is a creation b’tzelem Elohim (in the image of God), individuals are not expected to sacrifice themselves for the good of the whole. One classic Talmudic text illustrates this principle by describing a situation in which non-Jews demand, “Give us one of you or we will kill you all.” (Yerushalmi Terumot 8:4) Even though in most situations, Jewish law demands breaking other laws in order to save a life, in this case, the collective may not decide to sacrifice one of their members in order to save the rest. As Rav Moshe Avigdor Amiel (1883 1946) wrote in one of a series of essays criticizing both communism and fascism, “It is impossible to destroy an entire world [meaning a human being] for the sake of other worlds.”[6]

A society must concern itself with the needs of the whole — even when this means imposing taxes or restrictions on individuals — but must balance the good of the collective with the fundamental demands of human dignity and the infinite value of human life. A society may not subsume the individual into the whole, or — God forbid — justify sacrificing even a single life in service of the collective.

Controlled Capitalism

The past decades have seen an explosion in the number of billionaires, many of whose businesses employ hundreds or thousands of people who barely earn minimum wage and are unable to provide for their families’ basic needs. Jewish law does not forbid one from becoming wealthy but does place major checks on becoming wealthy off the backs of others. Thus, we find a host of laws preventing employers from exploiting their employees and even permitting townspeople to establish basic wages. Other laws ban business practices considered to be unfair competition, such as enticing children to visit one’s store by offering sweets or opening a business that threatens the livelihood of another. And an entire category of law prohibits charging excessive interest.

We have already seen the tzedakah fund — indeed multiple tzedakah funds — listed among the essential elements of a city. The Talmud, as well as volumes of later Jewish law, assumes tzedakah to be akin to a tax, not a charitable gift made out of a sense of altruism. Thus, collectors of tzedakah make assessments on individuals and may even collect from the wealthy by force. For this reason, tzedakah must be collected by two people, so as to prevent abuses, and is distributed by three people — the number that constitutes a beit din for monetary matters. (Bava Batra 8b)

Provisions such as these suggest a preference for controlled capitalism. There is no pretense of equal distribution of resources. But neither is there permission to become wealthy by any means, to exploit others for one’s own gain, or to keep all of one’s earnings for oneself.

An Independent Judiciary

The rabbis of the Talmud enumerate seven commandments considered to be given by God to Noah as part of the covenant after the flood, and therefore incumbent on all of humanity (Sanhedrin 56a). Among these is the establishment of a court of law. In order for residents to feel physically safe, as well as to be assured of justice in their business dealings, there must be a body entrusted to decide and enforce the law.

Seder Nezikin, the order of the Talmud discussed above, also considers how best to establish the judicial system. Principles guiding debates about judicial practice include a commitment to the dignity of both the alleged perpetrator and the victim, an insistence on establishing guilt beyond any doubt in instances in which capital punishment might be imposed, and a desire in financial matters to make the injured party whole, while also ensuring the broader society’s stability.

In one particularly confusing statement, the Talmud rules that a person convicted by unanimous decision of the court is thereby acquitted (Sanhedrin 17a). In attempting to explain this paradox, later scholars propose that a unanimous ruling may raise concerns of collusion or may indicate that judges did not try sufficiently hard to seek a strong defense.[7] A just court must be one whose independence can be trusted, and which refuses to privilege the claim of the plaintiff, even when the defendant might be entirely unsympathetic.

Robust Public Debate

It has become common to hold up the rabbis of the Talmud as exemplars of civil discourse. Many a rabbi and educator has specifically pointed to Hillel and Shammai, whose schools taught each other’s teachings, married one another’s daughters, and otherwise respected even differing opinions.

But any Talmud reader knows that while discussion is usually robust, it is often anything but civil. The rabbis regularly lob flowery insults at one another: “Go teach that outside [the study hall]” (Bava Kamma 34b and elsewhere); “If Levi [whose opinion you questioned] were here, he would take out rods of fire before you [and flog you]” (Bava Metzia 47a); “This one of the sages seems like one who has not studied halakha” (Bava Batra 84b).

What we have in the Talmud is not civil discourse but robust and often combative discourse. Even opinions considered too ridiculous to engage remain on the page.[8] The rabbis also understood that combative debate can lead to actual violence. In one instance rarely cited in extolling Hillel and Shammai, their students actually come to blows, with Shammai’s students murdering Hillel’s (Yerushalmi Shabbat 1:4, cf. Bavli Shabbat 17a). This day, the text says, “was as hard for Israel as the day on which the Golden Calf was made.” Debates may sometimes be nasty, but should not lead to blows.

The rabbis also understood the dangers of suppression of speech by autocratic rule. Criticism of Rome lands Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai in a cave for 13 years, escaping a death sentence. Even a rabbi who stays silent as an alternative to praising the empire finds himself exiled (Shabbat 33b). King Herod murders the rabbis lest they raise questions about his lineage. The one rabbi he leaves alive in order to provide counsel is, understandably, terrified to speak but manages to employ flattery in order to direct the king’s actions. (Bava Batra 4a)

So Does Judaism Believe in Democracy?

If we define a democracy primarily by means of elections and majority vote, classical Jewish texts do not even dream of this form of government. Other than a few instances of majority rule by the elites — rabbis and judges — and a few moments in which townspeople can weigh in on civil matters, classical texts do not offer any model of democratic rule.

However, if we understand democracy to require a commitment to strong public institutions, concern for the dignity and liberty of the individual, a responsibility of every individual toward the collective yet a refusal to subsume the individual into the collective, and an insistence on robust public debate, then we can find support for democracy in Jewish text.

But ultimately, the question of whether Judaism supports democracy is the wrong question. The Torah is eternal. Models of government come and go. Someday, some polity may invent a new form of government that works better than democracy. Crucially, though, Judaism offers a model by which to critique every government that comes our way. The biblical prophets do not hesitate to rail against the kings of their time, even when doing so may land them in prison. The Talmud minces few words when excoriating Rome for its sins. The rabbis even project themselves back in time to condemn the actions of the Hasmonean kings. And later Jewish writers, from legal experts to philosophers, and from ancient times to the present moment, dig deep into our sacred texts to critique the leaders, governments, and policies of their own times based on their success or failure in establishing a society that lives up to the vision laid out in our traditional sources.

NOTES

1“The Mounting Damage of Flawed Elections and Armed Conflict,” Yana Gorokhovskaia and Cathryn Grothe, (Freedom House, 2024) https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2024/mounting-damage-flawed-elections-and-armed-conflict.

2“Global Issues: Democracy,” (United Nations) https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/democracy.

3 The version of this list offered by Rambam (Moses Maimonides) adds a source of water, and leaves out the butcher. Otzar Midrashim, a 20th century compilation of earlier midrashim, offers a list of nine items: A synagogue, a yeshiva, a school for children, a court, a bathhouse, a fund for peddlers, a tzedakah fund, a mikvah, and fruit.

4 A third possibility, that people pay according to household size, is raised but not really considered.

5 For example, the 12th/13th century commentary Tosafot concludes: Rabbenu Tam (c. 1100-1171) explained, “The poor who live closer give more than those who live farther away, and similarly, the wealthy who live closer give more than the wealthy who live farther away, but the wealthy who live farther away give more than the poor who live closer, as we collect also according to wealth.” The Rambam is an outlier in concluding that proximity is the determining factor, without considering the factor of wealth at all. (Mishneh Torah Laws of Neighbors 6:4)

6“Tzedek haKlal uTzedek HaPrat” in Lenevuchei Hatekufah (Or Etzion, 2014) p. 120. The following essay, “Mesirat Nefesh Shel Haklal be’ad HaPerat,” more directly cites the case of being asked to hand over either a woman to be “defiled” or a person to be killed and makes a similar point, though I found this quote to be his most concise articulation of the concept.

7 See, for example, Rabbi Yehoshua Hartman’s notes on Gevurot Hashem 47:49.

8 Of course, many opinions presumably do not make it into our text, including the opinions of most of the women in the rabbinic milieu, as well as the opinions of non elites.

RABBI JILL JACOBS (she/her) is the CEO of T’ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights. She is the author of “Where Justice Dwells: A Hands-On Guide to Doing Social Justice in Your Jewish Community” and “There Shall Be No Needy: Pursuing Social Justice through Jewish Law and Tradition,” both published by Jewish Lights. She holds rabbinic ordination and an MA in Talmud from the Jewish Theological Seminary, where she was a Wexner Fellow; an MS in Urban Affairs from Hunter College; and a BA from Columbia University. She is also a graduate of the Mandel Institute Jerusalem Fellows Program. She lives in New York with her husband, Rabbi Guy Austrian, and their two daughters.