This week’s parshah opens with the command, “Give yourself judges and administrators to carry out just decisions…” (Deut. 16:18)

On the face of it, this seems to be about how society should be ordered. It needs police, judges, lawyers, and a whole mechanism of justice in order to function rightly. Rather than each individual carrying out vigilante justice, we delegate that role to people we deem worthy and to whom we grant authority.

But look again at the verb. Give yourself, not yourselves—the command is in the singular. Each of us is personally addressed by “God” to do just that: make judgments that are fair and just and carry them out, and pursue with just means the goals of justice, so that injustice, oppression, and anguished suffering are eliminated. It is our direct and immediate response-ability. Delegation here is a simple function of logistics, not a deep statement of principles.

The meaning of and reason for this commandment can best be understood by listening to teachings from The Prophets by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

The universe is done. The great masterpiece still undone, still in the process of being created, is history. For accomplishing God’s grand design, God needs the help of humanity…But God needs mercy, righteousness. God’s needs cannot be satisfied in temple, in space, but only in history, in time…Justice is scarce, injustice exceedingly common. The concern for justice is (not just) delegated to the judges, as if it were a matter for professionals or specialists.Justice is the active process of remedying or preventing…injustice. What is of uppermost importance to the prophets was the presence of oppression and corruption. The urgency of justice was an urgency of aiding and saving the victims of oppression.To do justice is what God demands of every person; it is the supreme commandment, and one that cannot be fulfilled vicariously. Concern for justice is an act of love.To love means to transfer the center of one’s inner life from your ego, to the object of your love.

This radical act of justice-as-love can spread forth to encompass society as a whole, but it starts with the individual. We see this in the Haftarah for Yom Kippur morning, where Isaiah (ch. 58) proclaims:

6 Is not this the fast that I have chosen? To loose the bonds of wickedness, to undo the bonds of oppression, to let the crushed go free, and to break every yoke? 7 Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and to take the outcast poor into your home? To clothe the naked and not hide yourself from your own flesh?

We could interpret verse six as being about broad structural changes—in our economy, our justice systems, our social services. Those are enormous problems that little old me can’t do much to influence. But verse seven brings the onus home: to the bread on my table, the poor person in my neighborhood, and—sometimes, paradoxically, hardest of all—the needy member of my own family.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev is said to have lamented, “Nowadays Jews tell lies in the street and the truth in the synagogues. Alas for the good old days when they used to tell the truth in the street and lies in the synagogues.”

Let us tell lies in shul if we must, but let us have honesty when it comes to taking responsibility for the injustice we see around us. Each of us, you and me, choose how we will personally respond to this Mitzvah which is personally addressed to each of us: “to pursue with just means what is just.” In every situation in which we find ourselves, we are called to justly pursue justice, as an act of love, compassion, and caring for our fellow human beings.

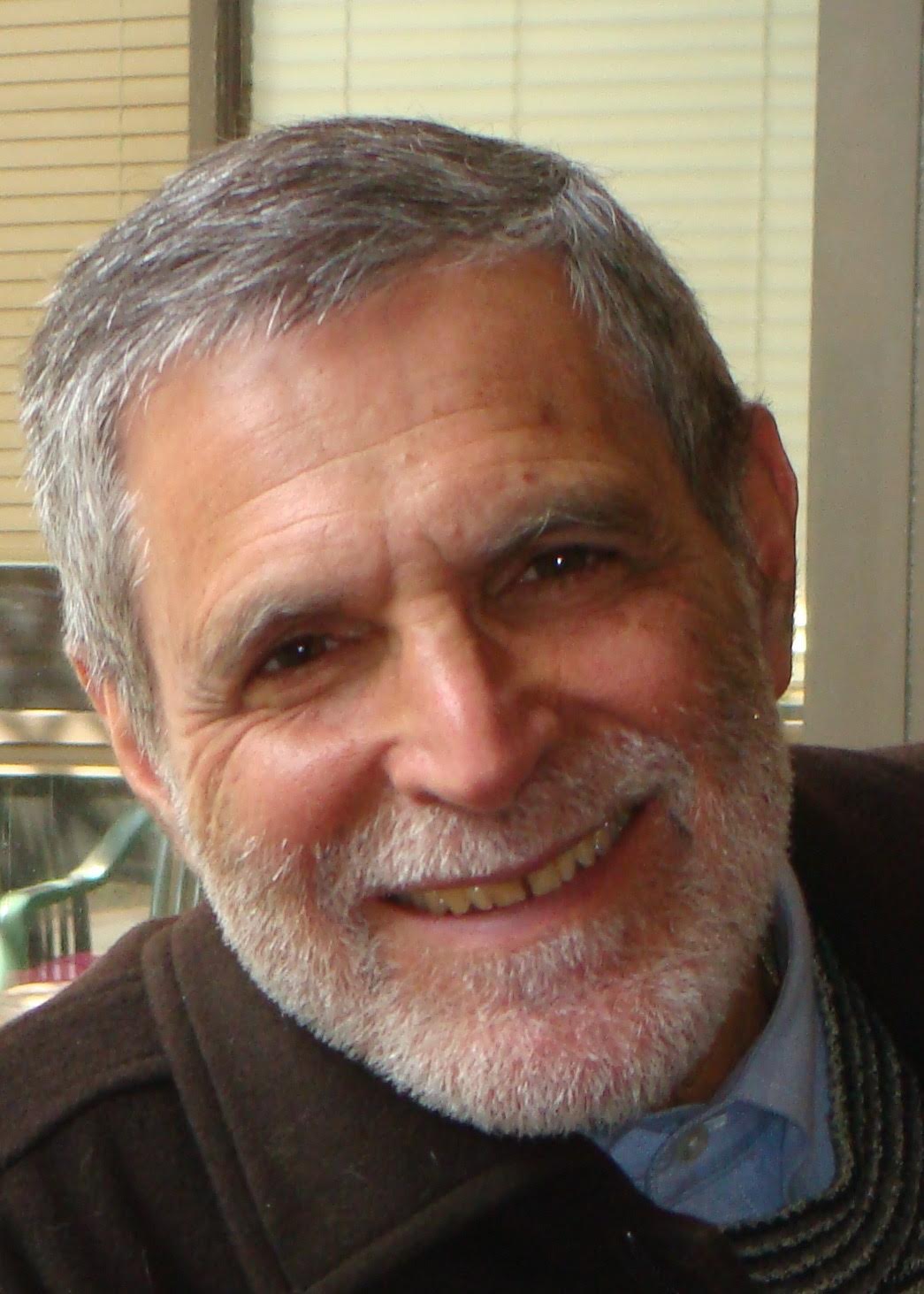

Rabbi Stan Levy is one of the two spiritual leaders of B’nai Horin – Children of Freedom, a community which he founded over 47 years ago. He is a co-founder of three public interest law firms – The Western Center on Law & Poverty, Public Counsel, and Bet Tzedek, where he is the founding national director of its Holocaust Survivors Justice Network. He is also a co-founder of The Academy for Jewish Religion, California, a post-denominational Rabbinical School, Cantorial School, and Chaplaincy School. He lives in Los Angeles with Lynda, his wife of 52 years, and is a senior counsel with the law firm of Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP.